In these times of turbulence and upheaval, I have often found myself turning to fiction – and particularly to alternate history. These are the “what if” stories that ask us to imagine our world on a different path: what if a battle, election or assassination had gone the other way, or a pivotal person had never been born? Some of these stories involve time travel to make the change, but many alternate histories are simply imagined differences. What if the Nazis had not been beaten, as in the novel The Man in the High Castle, or what if the Soviets had landed a man on the Moon first, like in For All Mankind?

No longer merely a subculture of science fiction, alternate history has become a realm of serious research, with historians involved in the study of counterfactuals. Meanwhile, enthusiasts gather on websites like alternatehistory.com to explore what the world of film and television might be like if Star Trek and Star Wars never existed, or if the lives of world-changing scientists had taken a slightly different path. There are even threads exploring how to construct portions of Wikipedia pages about events from alternate timelines.

But one of the deepest pleasures of alternate histories are their maps. Sometimes these allow stories to unfurl, or complement the hypothetical world of a tale being told. But in many cases, the map alone tells a story.

The writer Michael Chabon recognised the tantalising appeal of these maps when making his own while writing his novel The Yiddish Policeman’s Union, which is set in an alternate version of Sitka in Alaska. “I sensed I could get sucked in very easily to doing beautifully rich, detailed maps of Sitka and environs,” he told the Seattle Times, “so I tried to be strict with myself and just made crude pencil sketches that aren’t much to look at, to try to figure out where everything was.”

Chabon hit upon the attraction of imagined cartographies: the lure of making the paraphernalia of verisimilitude. These worlds are different but they could exist, and we can be easily sucked into spending too much time lavishing detail on these constructions. Some might say such maps are irrelevant to real life, but is there not delight in pretending to inhabit these worlds, imagining ourselves skimming across the landscape, dipping into fictional countries or cities, and thinking about what our lives might be like?

Such maps can also help us see the past and present with fresh eyes. For example, any alternate history is not simply a point of divergence, followed by seat-of-the-pants conjecture. True masters develop scenarios and fleshed-out histories, ones that simply beg for a slew of maps to go along with them. The alternate history textbook For Want of A Nail by Robert Sobel is such a scenario, exploring what if the United States had lost the American Revolution. Or, as this textbook from an alternate 1970s might put it, if the Rebellion had been crushed by the British Empire.

Below you can see snapshots of Sobel’s fictional North America, but helpfully, someone on the internet also generated a simple animation of how the political boundaries could have evolved. Small changes ripple outwards until the continent has become far from recognisable.

Another amateur map enthusiast online has explored the “1,000 Week Reich,” which they describe as a “realistic” Nazi victory scenario: “In basic terms, Germany signs an armistice with Britain in early 1941, wins the war against the USSR at great cost, and continues having to fight a guerrilla insurgency in Eastern Europe for years as Britain and America build a close alliance in opposition to them. A civil war breaks out and lasts through the mid-late 1950s, with Nazi Europe crumbling slowly, and direct Western intervention being the final death blow.” The Nazi Empire essentially peters out.

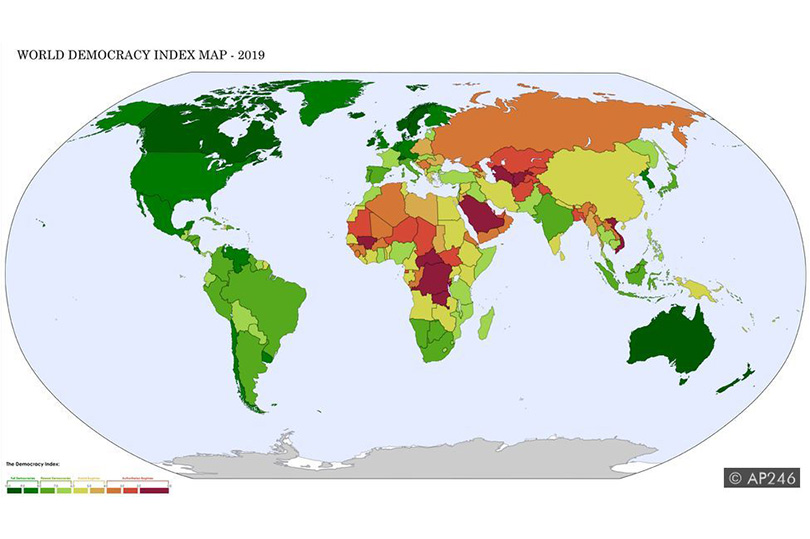

This scenario’s creator has generated numerous maps, and a rich fictional world. The map that I find the most intriguing from this scenario is the Democracy Index World Map from 2019. The map is incredibly detailed, and even rather dry, yet arises from an entirely parallel history to our own:

Another history that I find evocative is one that imagines the removal of President Andrew Johnson from office in 1867, by a coup d’etat. In the process, this history unspools a proportional representation system for the US, alongside so much more. It culminates in a rather bonkers map and imagined Wikipedia page of the 2018 American election (see below), which looks so real, using the apparatus of Wikipedia and real photographs, but is incredibly different from our own world.

Both the Democracy Index World Map and this fictional Wikipedia page are also wonderful examples of the love and attention to detail that is infused in many of these maps. A big part of these creations is not the content but the presentation: the aesthetic sense of the alternate world that the map itself describes.

For example, below is an alternate history map that looks like something out of The Economist magazine, followed by another lovingly-crafted map of what the Middle East might look like, if World War Two hadn’t happened.

The events of WW2 have been the inspiration for many more alternate histories, but one of the weirdest comes from the writer Harry Turtledove, who has published elaborate novels dealing in a wide variety of counterfactuals. One embodies what is known as the Alien Space Bats category of alternate history: what if, during WW2, aliens invaded Earth? This wild premise is explored in detail over the course of eight novels. The novels combine sci-fi ideas of interstellar travel and the technological paces of progress of different species, with historical concerns such as what might it mean if these reptilian aliens attack Nazi Germany and end the Holocaust, or a Cold War emerged between humanity and aliens?

But of course, any divergence can also be far earlier than the most recent few centuries. In The Years of Rice and Salt, the novelist Kim Stanley Robinson imagines the world if the Black Death had killed nearly all of Europe instead of one-third of the population. How would the other civilisations of the world have stepped into this void? How would technology and culture develop, and what would the outcomes of world wars be? You can see that map here, derived from the story. One of my favourite details from this fictional world is that the city that develops on the San Francisco Bay – for, of course, this natural bay is too perfect to be ignored – is located on the northern slopes of Marin county, rather than the southern side.

However, what if we dispense with requiring only a single point of divergence in history? For example, in American history there have been numerous plans for states that never quite went anywhere. But what if they all succeeded? Behold, the 124 United States of America. The map below distills huge amounts of politics, history, and the nature of the American psyche into a single image. The United States is a country that, despite its name, is also one that strives for separation and distinctiveness.

Or take the following delightful example of a map in search of a history. This is an alternate vision of the Americas made by high school student Anna Calcaterra, where she extended Texas all the way through Canada, included a mysterious “Ohio 2,” and renamed Minnesota as East Dakota. A lot is going on. A story must be intuited from the unbelievably strange nature of the world it displays. You look at this map, and you are forced to ask: what has happened here?

History is far from a linear path of progress or a tidy series of seminal dates to be memorised. It is messy: it involves small changes resulting in big differences, and many changes that simply might not matter that much at all. During times of tumult like the events of 2020, it can be difficult to see through all the complexity to predict what will actually mean a different world for us, or when a trivial change is simply that: trivial. Nevertheless, in the absence of clarity, we can always take delight in maps from worlds that never were.

* Samuel Arbesman is scientist in residence at Lux Capital and the author of “The Half-Life of Facts”, and “Overcomplicated”.

Comments