By Brian Chappatta

In many ways, all the talk about global central banks beginning a “great unwind” of their extraordinary monetary stimulus is positively quaint.

After all, how can officials from the Federal Reserve to the Bank of Japan even pretend to know how to reverse what they’ve done over the past decade? I’m speaking specifically about propping up financial markets with easy money and allowing the world’s debt burden to balloon to almost $250 trillion.

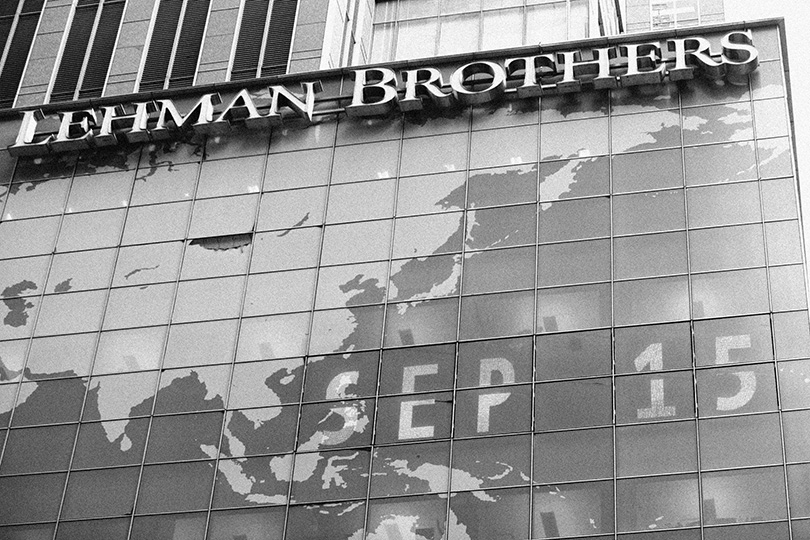

They kept interest rates at or below zero for an extended period — probably too long, if they’re being honest with themselves — and used bond-buying programs to further suppress sovereign yields, punishing savers and promoting consumption and risk-taking. Global debt has ballooned over the past two decades: from $84 trillion at the turn of the century, to $173 trillion at the time of the 2008 financial crisis, to $250 trillion a decade after Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc.’s collapse.

Governments are largely responsible for the borrowing binge, with their debt growing not just nominally...

...but as a percentage of global GDP as well.

Not everyone is piling up debt. Thanks to post-crisis regulations, financial corporations have become healthier and more resilient to another shock. Over the past decade, they’ve increased their debt by just $3 trillion, leaving their debt-to-GDP ratio as low as it has been in recent memory.

But other companies have picked up the slack, taking advantage of rock-bottom interest rates to take on increasingly high amounts of leverage to boost profits. They used to have less debt than financial corporations. Some $27 trillion of borrowing later, the obligations are almost as large as the world’s GDP.

Households across the globe appear to be in a similar position as they were 10 years ago. As a percentage of GDP, the debt has barely changed. But it depends where you look. In nominal terms, household debt is down in developed markets like the Germany, Japan and the U.K. In China, on the other hand, households have accumulated $6.5 trillion of debt, up from $757 billion in 2008.

Now, 10 years after the collapse of Lehman Brothers, we’re seeing the results of the grandest central-bank experiment in history. On the surface, it looks like mission accomplished. In the U.S., the unemployment rate is near a 48-year low, the S&P 500 Index recently reached another all-time high and consumers are about as confident as they’ve been this millennium. But dig a little deeper, and you’ll find that this road has been paved with debt, debt and more debt — and that it’s a one-way street.

Let’s start with the $15.3 trillion U.S. Treasury market, the world’s biggest bond market. Remarkably, it has tripled in size since August 2008. For context, in the prior 10-year period, it grew by “only” $1.5 trillion, even amid the beginning of the Iraq War. The totality of U.S. federal debt now makes up more than 100 percent of America’s gross domestic product.

Meanwhile, American households have been deleveraging, with their debt as a percentage of GDP reaching the lowest level since 2002. U.S. financial corporations have slashed their leverage as well, while other companies have brought their borrowing back up to levels last seen amid the heights of the crisis.

isn’t a uniquely American problem. Across the globe, government debt has soared over the past decade, both in nominal amount and as a percentage of GDP. While individuals and financial institutions have been busy getting their houses in order after the crisis, many large governments leaned on their captive buyer base — central banks — to binge on debt and pull forward economic growth.

The fact that central banks suppressed interest rates also encouraged nonfinancial companies to tap the bond markets early and often. Across the world, their debt load now represents more than 90 percent of GDP, up from about 77 percent in 2008, according to data from the Institute of International Finance. Sometimes those proceeds were put to productive uses, but often the corporations merely purchased their own shares, boosting the stock value.

Now, this isn’t solely a developed-market story, either. Emerging-market debt levels are much higher than they were 10 years ago, with yield-starved investors clamoring for dollar-denominated debt from places like Turkey and Brazil. Of course, those nations are now coming under pressure as the Fed raises interest rates, boosting the dollar and making it more costly for companies in those countries to repay their obligations. Across all emerging nations, nonfinancial corporate debt represents almost 100 percent of their GDP.

But it’s worth noting that China’s debt levels have exploded in the post-Lehman era. China is now saddled with almost $40 trillion of debt, compared with less than $30 trillion for all other emerging markets combined. In 2008, the group had $16 trillion of debt, while China only carried $7 trillion. The world’s second-largest economy is now coming to terms with rising corporate defaults.

No one knows for sure whether the leverage across the financial system is sustainable — only that it’s different from 2008. Back then, some individuals overextended themselves by taking on mortgages they had little hope of repaying. This time, companies are pushing the envelope as far as they can, accepting weaker credit ratings in an effort to maximize profits.

Sovereign governments, meanwhile, are in uncharted territory. While they can effectively print money with the help of central banks, no one is quite sure what happens when a global superpower like Japan reaches a debt-to-GDP ratio of 224 percent. The U.S., U.K. and France have all surpassed the 100 percent level.

Confronted with an aging population and promises of a social safety net, there’s no easy solution for how to counteract this trend. With the recession nine years in the rear-view mirror, this would typically be the time to pay off debt, not add to it.

Because of that, the fretting about the Fed’s current balance-sheet runoff plan is almost comical. There’s simply too much debt in the system and no clear path to truly paying it off. Not even central bank officials are pretending they’ll shed all their holdings — estimates fluctuate around ending at $2.5 trillion.

This is the post-Lehman legacy. To pull the global economy back from the brink, governments borrowed heavily from the future. That either portends pain ahead, through austerity measures or tax increases, or it signals that central-bank meddling will become a permanent fixture of 21st century financial markets.

Comments