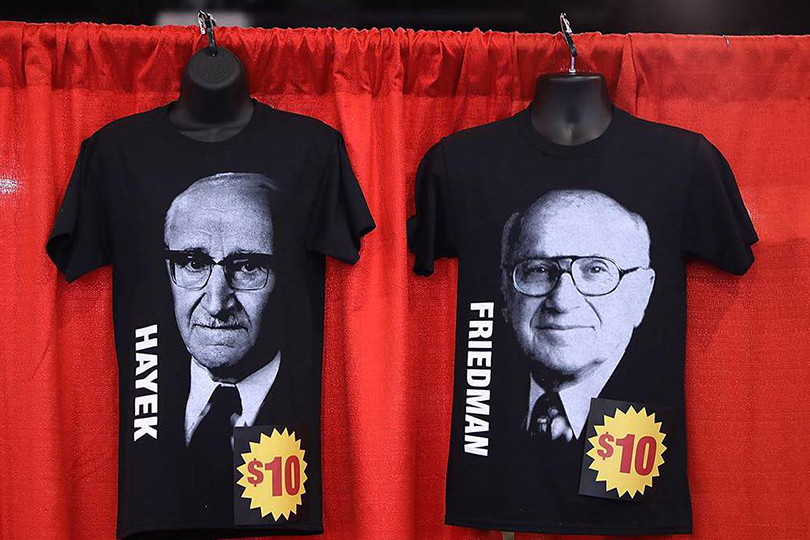

With politicians proposing policies that would vastly expand the size of the government and its involvement in the economy, it is clear that too many Americans have forgotten the lessons of the twentieth century. As Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman pointed out long ago, deviating from market principles is a recipe for disaster.

In our new book, Choose Economic Freedom, George P. Shultz and I point to clear historical evidence – and words of wisdom from Nobel laureate economist Milton Friedman – to show why good economics leads to good policy and good outcomes, while bad economics leads to bad policy and bad outcomes. But we also recognize that achieving economic freedom is difficult: one always must watch for new obstacles.

Many such obstacles are simply arguments rejecting the ideas that underpin economic freedom – the rule of law, predictable policies, reliance on markets, attention to incentives, and limitations on government. If an idea appears not to work, it must be replaced. Thus, it is argued that the rule of law should be replaced by arbitrary government actions, that policy predictability is overrated, that administrative decrees can replace market prices, that incentives don’t really matter, and that government does not need to be restrained.

These obstacles were common in the 1950s and 1960s, when socialism was creeping up everywhere. Many tried to stop the trend, and many were successful. But the same obstacles are now reappearing. For example, there are renewed calls for such things as occupational licensing, restrictions on wage and price setting, or government interventions in both domestic and international trade and finance.

Even the Business Roundtable is weighing in, announcing last August that US corporations share “a fundamental commitment to all of our stakeholders,” including customers, employees, suppliers, communities, and, last on the list, shareholders. That is a significant departure from the group’s 1997 statement, which held that, “the paramount duty of management and of boards of directors is to the corporation’s stockholders; the interests of other stakeholders are relevant as a derivative of the duty to stockholders.” Moreover, as that earlier statement was right to point out, the idea that a corporate board “must somehow balance the interests of stockholders against the interests of other stakeholders” is simply “unworkable.”

Following the demise of the Soviet Union, real-world case studies that showed the harms of excessive government intervention and central planning were forgotten. There are no longer discussions about how centrally imposed plans might lead a Soviet production plant to complete its objective by producing one 500-pound nail instead of 500 one-pound nails. Three decades after the fall of the Berlin Wall, it is understandable that today’s undergraduate students are unfamiliar with the risks of deviating from market principles.

That is why we need to teach history. What was said in the past is often the best reply to renewed claims in favor of socialism. In his introduction to the Fiftieth Anniversary Edition of Friedrich Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom, Friedman pointed out that the book was “essential reading for everyone seriously interested in politics in the broadest and least partisan sense, a book whose central message is timeless, applicable to a wide variety of concrete situations. In some ways, it is even more relevant to the United States today than it was when it created a sensation on its original publication in 1944.”

In 2020, the book is more relevant still. Its key message is that the benefits of market-determined prices and the incentives they provide far exceed anything that could come from central planning and government-administered prices. In his 1945 essay “The Use of Knowledge in Society,” Hayek explained that the problem of optimizing the use of available resources in an economy “can be stated best in mathematical form: … the marginal rates of substitution between any two commodities or factors must be the same in all their different uses.” But, he hastened to add, “This … is emphatically not the economic problem which society faces,” because “the ‘data’ from which the economic calculus starts are never for the whole society ‘given’ to a single mind which could work out the implications and can never be so given.”

Nowadays, students sometimes ask me why they need to study market economics at all. With artificial intelligence and machine learning, won’t governments soon be able to allocate people to the best jobs and make sure everyone gets what they want? Hayek’s old answer to that kind of question is still the best.

This is hardly the first time that the American political system has lurched toward massive expansions of government power and spending. In 1994, Friedman, in a New York Times article titled “Once Again: Why Socialism Won’t Work,” lamented that, “the bulk of the intellectual community almost automatically favors any expansion of government power so long as it is advertised as a way to protect individuals from big bad corporations, relieve poverty, protect the environment or promote ‘equality.’ … The intellectuals may have learned the words but they do not yet have the tune.”

Fortunately, there are still many ways to expand economic freedom and protect it from renewed encroachments. The point to remember is that government programs have costs as well as benefits. There is not just market failure but also government failure. And there are indeed private remedies to economic externalities. But if markets are to work, and if economic efficiency and liberty are to be achieved, the rule of law needs to be front and center, with clear monetary- and fiscal-policy rules in place.

Moreover, a wealth of new data can now help us demonstrate the benefits of economic freedom more widely. The Heritage Foundation’s Index of Economic Freedom, the Fraser Institute’s Economic Freedom of the World, and the World Bank’s Doing Business rankings are each published annually. Taken together, these reports show that good and bad economic outcomes in countries correlate strongly with good and bad policies. The stories behind the data are fascinating, and they can tell us what works and what does not.

But even if we shoot down all the arguments against economic freedom, there will still be obstacles to its realization. Moving forward requires that we put the ideas of economic freedom into practice. Otherwise, as Friedman put it in his 1994 introduction to Hayek’s book, “it is only a little overstated to say that we preach individualism and competitive capitalism, and practice socialism.” To get the job done, people must be clear about the principles, explain them, fight for them, and decide when and how much to compromise on them.

Comments