Dave Sheinin

Time zone by time zone, the people of the world awoke Saturday to the cold realization that it would be the first day in 74 years without Muhammad Ali in their midst. Though it could not have been a surprise, the great heavyweight champion’s death Friday night of complications from Parkinson’s disease left a massive void, one that people famous and common tried to fill with words. In many cases, words failed.

“You don’t want to live in a world without Muhammad Ali,” boxer George Foreman said of his former adversary. “It’s horrible.”

“The sadness,” wrote soccer legend Pelé in an Instagram post, “is overwhelming.”

Ali was hospitalized Monday in Scottsdale, Ariz., with respiratory issues and died Friday at 9:10 p.m. Mountain time, according to family spokesman Bob Gunnell. The official cause of death, he said, was “septic shock due to unspecified natural causes.” In his final hours, Ali was surrounded by his nine children and wife, Lonnie.

“They got to spend quality time with him to say their final goodbyes,” Gunnell said of Ali’s family. “It was a very solemn moment. It was a beautiful thing to watch because it displayed all that’s good about Muhammad Ali. . . . He did not suffer.”

Gunnell said funeral proceedings would take place in Ali’s home town of Louisville, with a private, family-only ceremony Thursday, followed Friday by a procession through the streets of Louisville, a private interment at Cave Hill Cemetery and a public, multi-faith memorial service with eulogies delivered by former president Bill Clinton, broadcaster Bryant Gumbel and comedian Billy Crystal. Among the officiants will be Sen. Orrin G. Hatch (R-Utah), a former Mormon bishop and a friend of Ali’s.

The funeral plans were made by Ali himself, years in advance, Gunnell said.

On Saturday, Ali’s death was greeted like that of a head of state, which, in a sense, he was. His classic fights in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo), the Philippines, Japan, England, Malaysia and Germany were global events in the days before the Internet made everything a global event. For a time, he was considered the most famous person in the world. A figure who transcended the boundaries of sport and country, he may have been the greatest ambassador the United States ever employed.

“Muhammad Ali shook up the world. And the world is better for it. We are all better for it,” President Obama said in a lengthy statement. “Michelle and I send our deepest condolences to his family, and we pray that the greatest fighter of them all finally rests in peace.” Obama later telephoned Ali’s widow, Lonnie, to express his condolences, the White House said.

Tributes from everywhere

Tributes to Ali came from all over the world, tracing the path of the sun as it rose and revealed the news. Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull tweeted, “Athlete, civil rights leader, humanitarian, man of faith. Rest in peace.” British Prime Minister David Cameron tweeted, “Muhammad Ali was not just a champion in the ring — he was a champion of civil rights, and a role model for so many people.”

In South Africa, many fondly recalled Ali’s visits in the 1990s to see President Nelson Mandela. “Together with Nelson Mandela, Ali was a source of inspiration for those who pursue justice, those seeking equal opportunities, the downtrodden and those seeking fairness in sport and society,” said Danny Jordaan, the head of the country’s soccer federation, in a statement.

The leader of Kenya’s political opposition, Raila Odinga, said in a statement: “Muhammad Ali fought for the emancipation of the black race not only in the U.S. but also in many African nations then under the yoke of colonialism.”

Paul McCartney, one of few humans whose worldwide popularity could match Ali’s, wrote in a statement posted on his website, “I loved that man. . . . Besides being the greatest boxer, he was a beautiful, gentle man with a great sense of humour.”

Former Presidents Clinton and George W. Bush also paid tribute to Ali for the inspiration he provided millions as a boxer and humanitarian, and later in life for the dignified manner in which he fought his disease.

In Louisville, the U.S. flag was lowered to half-staff at City Hall. “Muhammad Ali belongs to the world,” Mayor Greg Fischer said at a brief memorial Saturday. “But he only has one home town.”

Religious beliefs

The question of belonging — of ownership — was a central issue of Ali’s complex life outside the ring. To whom did he belong? Wearing the red, white and blue, he won the 1960 Olympic gold medal in Rome as Cassius Clay, but several years later embraced the Nation of Islam, changed his name to Muhammad Ali and disavowed “Cassius Clay” as his “slave name.” He later refused to serve in the Vietnam War, citing his religious beliefs, a stance that cost him his heavyweight crown in 1967.

“He sacrificed the heart of his career and money and glory for his religious beliefs about a war he thought unnecessary and unjust,” the Rev. Jesse Jackson, the civil rights leader, said in a statement. “His memory and legacy lingers on until eternity. He scarified, the nation benefited. He was a champion in the ring, but, more than that, a hero beyond the ring. When champions win, people carry them off the field on their shoulders. When heroes win, people ride on their shoulders. We rode on Muhammad Ali’s shoulders.”

Basketball Hall of Famer Kareem Abdul-Jabbar wrote in a Facebook post late Friday night, “Today we bow our heads at the loss of a man who did so much for America. Tomorrow we will raise our heads again remembering that his bravery, his outspokenness, and his sacrifice for the sake of his community and country lives on in the best part of each of us.”

Donald Trump, the presumptive Republican presidential nominee, deployed a pair of exclamation points in a tweet about Ali’s death — “Muhammad Ali is dead at 74! A truly great champion and a wonderful guy. He will be missed by all!” — though more than one commentator noted the irony of Trump praising Ali.

In December, after Trump proposed banning Muslims from entering the United States, Ali responded in a statement. “Our political leaders should use their position to bring understanding about the religion of Islam and clarify that these misguided murderers have perverted people’s views on what Islam really is,” Ali wrote.

In Pakistan, where Ali was widely regarded as the world’s most iconic sports figure, there was an outpouring of grief over his death. Boxing is a popular sport in Pakistan, and the country’s overwhelmingly Muslim population saw Ali as an inspiration for combating xenophobia in the West.

Recovering from heart surgery in London, Pakistan Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif issued a statement saying Ali was an “inspiration for not only young Americans, but also young men and women of the world.”

Sharif continued: “His legacy has not only impacted modern boxing, he has also been an instrumental figure in changing social, political and religious narratives surrounding minorities in the West and for that, we are in his debt. The world is truly poorer without him.”

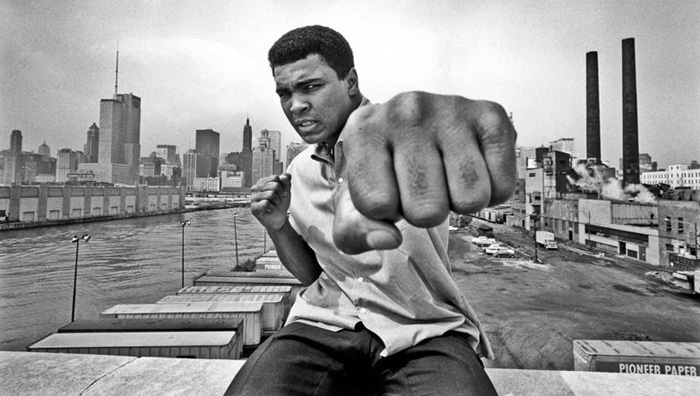

Indelible images

Where words failed to pay proper tribute to the man who called himself “The Greatest of All Time,” people tried photos, videos, GIFs.

There he was frozen in time, standing over Sonny Liston in 1965. There he was, in the corner of the ring, bobbing his head and dodging 21 straight punches. There he was, answering interview questions with a combination of poetry and braggadocio. And there he was, lighting the Olympic cauldron at the 1996 Atlanta Summer Games, the torch trembling in his hand — the iconic image from the later stages of his life.

In the United States, cable news networks went wall to wall with Ali news and reactions all day Saturday. There were no shortage of celebrities and journalists willing to go on air. People flocked to YouTube, where some of his classic fights live on. On social media, millions who never met him described how he had nevertheless touched their lives.

It was all a reaction Ali appeared to have foreseen. In his 2004 memoir, “The Soul of a Butterfly: Reflections on Life’s Journey” — a collaboration with his daughter Hana Yasmeen Ali, he addressed the question of how he would like to be remembered, writing:

“I would like to be remembered as a man who won the heavyweight championship three times, who was humorous, and who treated everyone right. As a man who never looked down on those who looked up to him, and who helped as many people as he could. As a man who stood up for his beliefs no matter what. As a man who tried to unite all humankind through faith and love. And if all that’s too much, then I guess I’d settle for being remembered only as a great boxer who became a leader and champion for his people. And I wouldn’t’ even mind if folks forgot how pretty I was.”

Comments