Michael Rubin

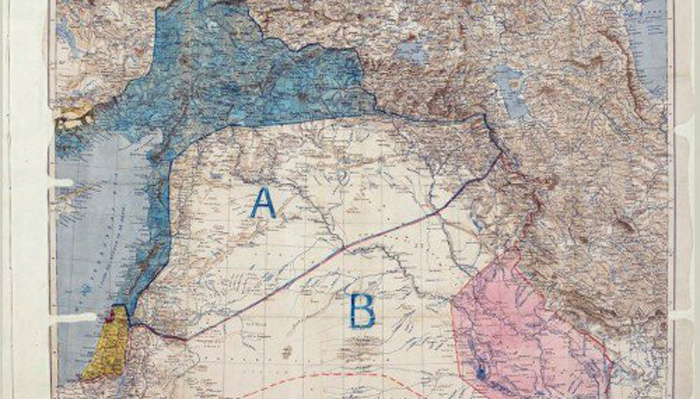

May 16 marks the 100th anniversary of the Sykes-Picot Agreement, a secret deal which divided up the heart of the Middle East (and would have divided up Turkey as well, had it not been for the intervention of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk). Robin Wright, a frequent writer on the Middle East, recently penned an article calling Sykes-Picot “a curse.” Nonsense. Sykes-Picot was a blessing for many in the Middle East.

To look at the map of the Middle East might be to conclude that Sykes-Picot, the agreement which led to the drawing of so many contemporary borders, also created artificial countries. But just because a border is artificial does not mean that the resulting county is.

Iraq, for example, became independent in 1932, twelve years after the League of Nations demarcated its borders, but Arabic literature speaks of “Iraq” going back a millennium. Likewise, Syria — under its current artificial borders — became a League of Nations’ Mandate in 1920, but a notion of Syria as a region existed at the time of Muhammad. The same holds true for Turkey and Israel. Mount Lebanon has always had a unique identity, not the least because of the Maronite Christian presence. Syria itself, however, never recognized the Lebanese identity but the divisions of Sykes-Picot enabled the Lebanese among others to win freedom.

Did anyone lose in the Sykes-Picot Agreement? After a free trip to Iraqi Kurdistan, Wright quotes Kurdish officials to suggest the Kurds did, although the history is a bit more complicated than that: The Kurds lost out not because of the Sykes-Picot Agreement, but because of machinations of great powers in its wake, confirmed first in the Treaty of Lausanne and subsequently by a League of Nations commission to adjudicate a continuing dispute about the Vilayat of Mosul.

Did Sykes-Picot also create artificial countries? Certainly. Jordan is the primary case in point. Similar arguments are often made about the Gulf Cooperation Council states, despite not being born as the result of Sykes-Picot. The smaller among them may effectively be “tribes with flags,” but even that is a real identity.

Is it possible to rectify past mistakes? Certainly. The Kurds may win their independence, although to do so today without internal problems resolved would likely result in Kurdistan joining South Sudan, Kosovo, East Timor, and Eritrea as a failed stated. But is discussion about reversing the legacy of Sykes-Picot counterproductive? Absolutely.

First, after nearly century of nationhood, many of the states which emerged as a result of post-World War I divisions have attained specific identities distinct from their neighbors. One hundred years of history is a lot to reverse.

Second, to counsel reversing Sykes-Picot and to start again is effectively to double down on imperialism. There is no way to divide borders and create homogeneous states. To even try to is to conduct ethnic and sectarian cleansing. To create new borders and new states with minority populations, meanwhile, is simply to reshuffle the deck, not change the game.

Thirdly, to suggest the pre-Sykes-Picot order was desirable is, in effect, to return to the Ottoman millet system of basing governance upon religion. This would affirm the Islamic State, not reverse it. And it would do nothing to help those seeking statehood based on ethnic notions of nationalism.

It’s certainly become vogue to bash imperialism, colonialism, and the West’s legacy. But sometimes what is stylish is not necessarily right. Rather than lament Sykes-Picot, let’s recognize it for what it was: a mechanism born in imperial cynicism which nonetheless provided an opportunity (often missed) for freedom and national aspiration.

Comments