Throughout the Western world, sympathies for right-wing strongmen are gaining strength. In the U.S., Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump are tied in the polls. In Austria, it came to a showdown between the Green candidate Alexander van der Bellen and the right-wing nationalist Norbert Hofer. These societies are split 50-50, right down the middle.

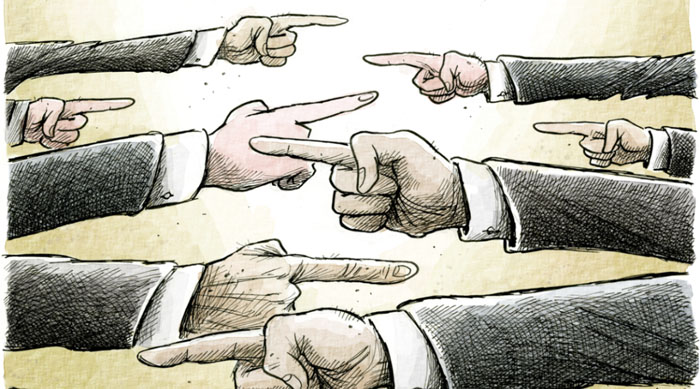

For Germany, such results have long been the norm. It hasn’t succumbed to radicalism, but it is a sobering parliamentary reality that in two or three previous and current legislatures, the Social Democrats and the Christian Conservatives are forced to govern together. This leads to a stalemate, since the most important issues of the future cannot be addressed in deadlock. Compromises, the lifeblood of democracy, are always stretched to their max under such configurations — and sometimes they are overstretched.

This is probably why people here are looking towards Austria with such apprehension: a sudden jump to the right or the left has never been good for Germany. Our Alpine neighbor was prepared to swear in a far-right president. In the end, the man from the Greens, the more moderate candidate, won the election by the slimmest of margins.

The Green Party has long been a refreshing presence on the European party spectrum. But still, Hofer got half the vote in an election that, by the way, had a record turnout of almost 72 percent. Has a radicalization of the political scene, with voters pushed to the edges of the spectrum, revitalized democracy?

Observers have discerned that democracy, and liberal democracy in particular, is something that must be fought for. Throughout the Western world, neo-national, anti-Islamic, homophobic and gender-hostile political forces have been agitated. With record results, they’re able to get out of the stands and into state parliaments, as we can see with the Alternative for Germany party. Next year, there will be a federal election in Germany. What role will the AfD play?

The fight for democracy itself is also being led from the right by the likes of Hofer, Trump and Le Pen in France. They argue for the purification of democracy from the evils being inflicted on it by certain minority groups. For them, democracy is the rule of the majority over the minority. Liberal democracies, on the other hand, as they have taken shape in the countries of the West, inversely derive their value, their functionality and their legitimacy by how well they treat minorities.

The trend has, for a while, been going the opposite direction. People are now asking: What does it means to be French? What it means to be English? What it means to be German?

In a globalized world, where all people are digitally connected to one another, questions of identity are crucial. Outside the West, some groups dream of homogeneous places: the expulsion of Christians from the Middle East is due to the so-called Islamic State’s dreams of homogeneity and superiority. The same goes for the Hindu national dream of the current government in India.

The election in Austria is therefore just an appetizer. There’s the Brexit referendum in England at the end of June, opinions on which are also split right down the middle, and the election in November in the U.S., where society again appears to be split down the middle.

Austria is a small country and, on today’s global political stage, insignificant — though anyone visiting Vienna immediately notices that it was once the seat of a great empire. This applies similarly to Paris and London. A return to former greatness, a mission evoked by Trump in the U.S., can be heard also in France, England and Austria with similar rhetorical fashion.

I’m afraid Austria is just the beginning.

Comments