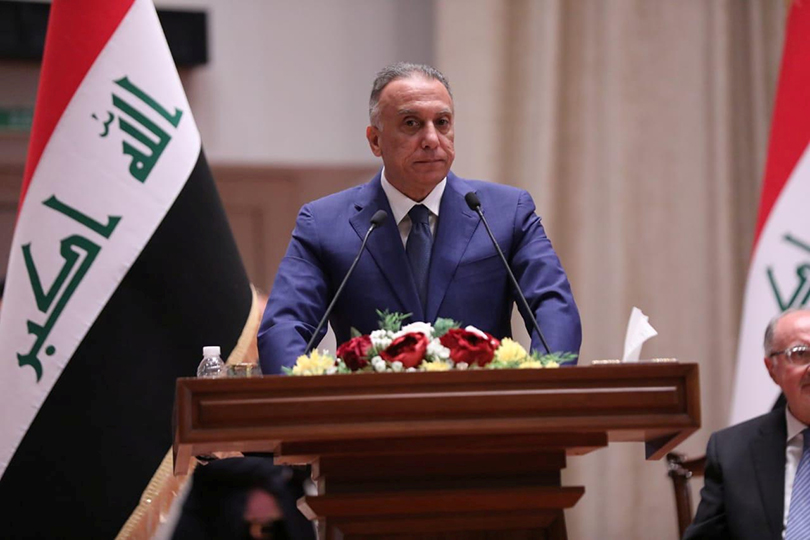

On June 25, Iraq’s Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi launched a raid against an Iran-aligned militia that has carried out at least 35 rocket attacks on U.S. targets in Iraq since last October. One such attack, in December, killed an American civilian contractor and wounded several U.S. military service members, triggering a series of events that culminated in the U.S. assassination of Iranian commander Qassem Soleimani and Kataib Hezbollah leader Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis in January. In the recent raid, Iraq’s Counter Terrorism Service arrested 14 members of Kataib Hezbollah, who were reportedly in the process of launching yet another attack.

Rocket attacks by Iranian proxy groups in Iraq have been a common feature of the Iraqi security landscape over the past two decades, often causing material damage and on occasion killing and injuring Americans and Iraqis. They add to a plethora of existing woes, as Iraq struggles to stabilize the country and revive its economy after months of social and political unrest, the decline in the oil price, and the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, the raid failed to re-assert the Iraqi state’s authority on the group, and events since the operation have indicated it may have actually been carried out in consultation with Iran and its allies. Kadhimi should avoid the temptation to secure short-term victories and focus on long-term plays to drive economic growth and political coalition-building. That will be the more sustainable way of containing Iran and preventing its proxies from carrying out attacks on U.S. targets in Iraq.

THE RAID AND ITS AFTERMATH

In the raid against Kataib Hezbollah, Kadhimi’s message was simple: Shiite militia groups in Iraq can no longer operate with impunity. The operation was audacious insofar as it could have prompted an armed response from the group, disrupting the fragile political consensus that enabled Kadhimi’s appointment two months ago.

However, the events that followed the raid have done little to carry Kadhimi’s message. It appears very probable that the operation was carried out in coordination or consultation with Iran and Iran-aligned political actors. For instance — whether out of sheer luck, or prior coordination with Iran or the leadership of militia groups and parliamentary blocs — the group did not respond in a major way. After the raid, Kataib Hezbollah mobilized a force of roughly 150 fighters in nearly 30 pickup trucks around the prime minister’s residence, which was designed to intimidate Kadhimi but avoid escalating the crisis into an armed confrontation.

Moreover, it was telling that the militiamen captured during the raid were placed under the supervision of the security directorate of the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), the umbrella militia organization that is dominated by Kataib Hezbollah and other Iran-aligned groups. The directorate is led by a Kataib Hezbollah commander. Therefore, the group was essentially able to get the prime minister to release the suspects into its own custody and deter the government from escalating the crisis in the process. On Monday, the militiamen were then, unsurprisingly, released by the PMF’s security directorate on the basis that there was insufficient evidence to prosecute them.

A CONUNDRUM

Kataib Hezbollah is struggling to regain the political preeminence it enjoyed under al-Muhandis’ leadership, whose long-standing relationships and personalized command of the political environment underscored the organization’s ascent in recent years. Unlike its rivals like the Badr Organization (which controls key Iraqi institutions and leads the second-largest political bloc in parliament) and Asaib ahl al-Haq (which is part of that same bloc and has 15 members of parliament to its name), Kataib Hezbollah lacks the same organizational discipline, as well as political and institutional reach.

However, the Iraqi government should not be complacent. Kataib Hezbollah still has substantial combat capabilities and has the capacity to violently confront Iraqi security forces. Those security forces would struggle to secure an outright military victory against the group. Were such a battle to occur, the group would also mobilize other powerful Iranian proxy groups against the government.

Kadhimi’s willingness to go after Shiite militia groups despite the constraints of his security forces will win him some plaudits in Iraq and the U.S. ahead of the U.S.-Iraq Strategic Dialogue in Washington this month. The prime minister is determined to improve Iraq’s relationship with the U.S., which will be critical to securing the lasting defeat of ISIS, reviving the economy, generating financial and technical support from the international community, and ensuring that Iraq does not become entangled in the U.S. maximum pressure campaign against Iran.

But Kadhimi now faces a conundrum: The raid on Kataib Hezbollah has exposed the government’s constraints, yet Iraqis and others now expect him to continue to assert his authority over the group and its affiliates. Kadhimi has put his credibility at stake. Does he go after the group again, even if that could trigger a conflict or provoke Iran and its other proxies? Kadhimi has a set a precedent that potentially sets him up for failure and humiliation.

Most importantly, attempts to curtail Iran’s proxies could harm the broader reform process, which is critical to forestalling a socio-economic implosion. Powerful groups (including Iran-aligned parties, and proxies in particular) that have a vested interest in sustaining the status quo have stymied that process. Although rocket attacks on the U.S. undermine security and harm U.S.-Iraq relations, it is also possible that Kadhimi (and the U.S., to the extent it is encouraging him both advertently and inadvertently) is falling into a trap that is designed to destabilize the political environment, reinforce political resistance against his premiership and reforms, and set him up for a conflict that plays into the hands of Iran and its proxies.

EYE ON THE PRIZE

Rather than provoke a conflict with militia groups that the government neither wants nor is likely to win, Kadhimi should remain firmly focused on Iraq’s economic regeneration and keep global attention focused on his government’s steadfast commitment to stabilizing the country and meeting the urgent needs of the Iraqi population. His government faces long-term structural challenges, including the stranglehold that Kataib Hezbollah and other Iranian proxies have on the formal and illicit economies, but the next three months will be critical as Iraq attempts to showcase its willingness and capacity (to audiences at home and abroad) to revive the economy. It is precisely the reform process — Kadhimi’s most powerful weapon — that will ultimately sideline Iran’s proxies and win the hearts and minds of Iraqis.

Security in Iraq is politics: Suppressing militia groups like Kataib Hezbollah cannot be a half-hearted effort. If Kadhimi and the U.S. are serious about containing Iran-aligned groups, there needs to be a firm commitment and a willingness to go all the way — and with a political strategy to manage potential fallout for governance and reform in the country. This could come into play when small windows of opportunity emerge, precipitated by Iraq’s volatile political and security environment. Washington has preferred a tit-for-tat approach to conflict with Iranian proxy groups, but the U.S. risks inadvertently encouraging Kadhimi into a conflict with Iran, for which he currently lacks the capacity.

Rather than encourage Kadhimi to mobilize his forces against Iran’s proxies and fall for the bait Iran has set, the U.S. must determine if it is willing to provide him with a military safety net that would help back him up if he decides to move against these powerful groups. Secondly, the U.S. should avoid the mistakes of the past and not rely only on the prime minister. Washington should encourage and work with Kadhimi to devise a strategy that musters an impervious political coalition within the Iraqi parliament.

Kadhimi will undoubtedly make enemies along the way, but he should ensure they are the right enemies (i.e. the malign actors that have no interest in a prosperous Iraq and want to force the U.S. out of the country). With U.S. support, Kadhimi can move to establish a political coalition that is underpinned by groups — including Arab Sunni, Shiite, and Kurdish political actors — that want to work with him to secure continued U.S. support and a continued American presence in Iraq.

This alliance can also help the government ensure that the PMF and Iran-aligned groups do not capture and subvert its reforms, and could insulate Kadhimi from any fallout after future attempts to suppress Iran’s proxies. These actors would similarly provide the building blocks for a coalition that provides Kadhimi with a viable electoral bloc to contest the next parliamentary elections. The ultimate goal is to protect the reform process from being torpedoed. Washington, for its part, can help mediate tensions within the alliance. Coalitions in Iraq are often fractious and susceptible to Iran’s divide-and-conquer political tactics in Iraq.

Where attacks on U.S. targets are imminent, Iraq must respond, but that should be underscored by a political strategy and a coercive capacity that Washington reinforces. Focusing on long-term plays as opposed to short-term tactical victories is key to ensuring the government does not play into Iran’s hands, making mistakes that make a mockery of Iraqi sovereignty and its judicial process. Rather, Kadhimi must focus on establishing a multi-pronged, piece-by-piece approach to containing Iran and ending rocket attacks that have killed and injured Americans and Iraqis alike.

Comments