Gordon Brown

Article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that every child should have access to free primary education. Yet, 69 years after that pledge, a record number of children – some 70 million – are caught in the crossfire of humanitarian crises that are denying them schooling and placing their futures in jeopardy.

For nearly seven decades of a tumultuous century, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights has served as a beacon of hope worldwide. But some of its finely crafted provisions have come back to haunt us in the form of some shocking new statistics.

Article 26 of the declaration states explicitly that every child has the right to free primary education. Yet, 69 years after that pledge, a record number of children – some 70 million – are caught in the crossfire of humanitarian emergencies that are denying them basic rights and placing their futures in jeopardy. Of these, more than 31 million girls and boys are displaced from their homes, and 11 million have been forced to flee their countries.

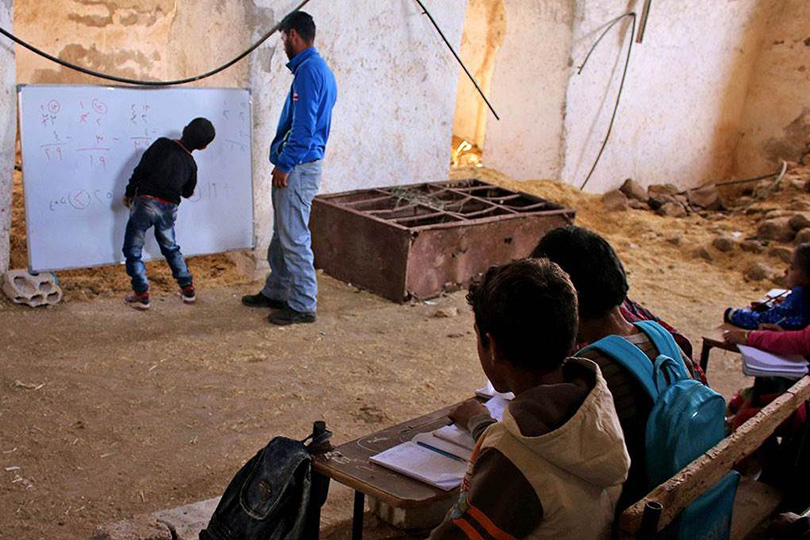

Compared to other children, young people displaced by conflict and crisis are half as likely to attend school. Not surprisingly, they are also the most likely victims of child labor, child marriage, and child trafficking – an unholy trinity that should weigh more heavily on the world’s conscience than it does. Of the 70 million children in peril, two in five have personally experienced violence or abuse. And although many of these children will likely never enter a classroom, school is precisely where they want – and need – to be.

“I don’t want to die,” one terrified girl begged from a war zone, “just study.” But, writing to a friend in the United Kingdom, she added defiantly: “I’m still alive, and my dreams are, too.” Her escape, her hope, and her heart all revolve around education.

The total number of children ensnared in emergencies – a figure that has grown by five million in just a few short years, and today outnumbers the population of France – will only worsen in 2018 if we fail to act decisively.

Global humanitarian response plans for the coming year, coordinated under the leadership of Mark Lowcock and the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), will now place greater emphasis on displaced children’s educational needs, with particular support for girls at risk of being forced into marriage. But, despite the courageous efforts of aid agencies, conditions may still deteriorate before they improve. In Bangladesh, for example, more than 300,000 child refugees have been forced out of their homes as a consequence of sectarian violence in neighboring Myanmar. And while most refugees there have received food assistance, health care, and emergency shelter, only one in ten – some 30,000 children – are currently attending school, because only 5% of the humanitarian aid needed to educate Myanmar’s refugee children has been met.

While it is a remarkable achievement that one million Syrian children are now enrolled in formal or non-formal education programs in the region – including many in schools running on double shifts – one million more refugee children from that conflict are still awaiting their opportunity. Another 1.7 million children are out of school within Syria itself.

There can be no excuses for our failure to provide an education to children in the 19 global crisis zones that have suffered emergencies for five years or more, especially in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Sudan, and Somalia – where crises have persisted for over 20 years. In the DRC, for example, even after all this time we reach only 8% of the 760,000 children. Only $230 per year per person is available for basic needs such as water, food, and shelter, and less than $10 per child goes toward education.

This year must be education’s moment – a window of opportunity opened by a new consensus that education is critical to achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goals, including reducing maternal and infant mortality rates, spurring job creation, improving quality of life, and opening our minds to issues of gender equality. But, most important, this is education’s moment because the world’s young people are demanding it.

When a girl holds a book up to an insurgent’s gun in Pakistan, when teenage mothers exiled from South Sudan in neighboring Uganda make education for their children their top priority, and when lights seen from space might include clusters of children huddled by candlelight trying to read and study, we know that education’s moment has come. Education provides hope – hope that a child can plan and prepare for a future defined by opportunity, not by child labor, marriage, or a life on the streets.

Comments