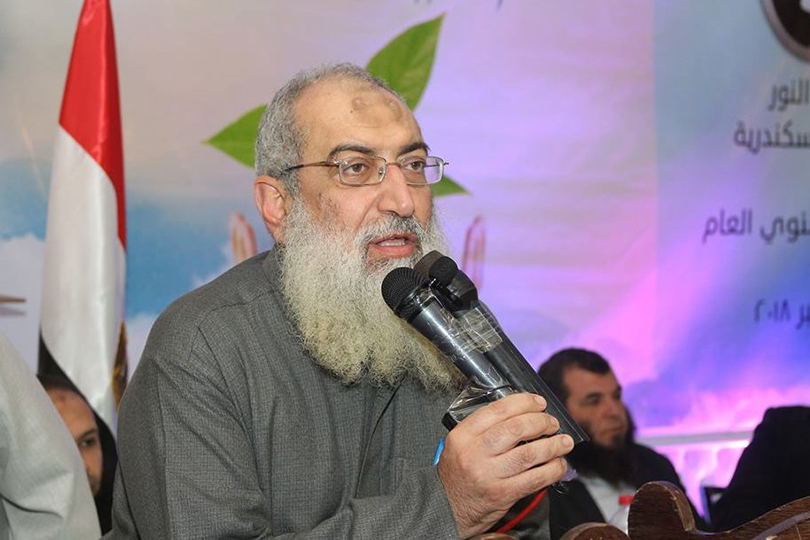

Egypt's Ministry of Religious Endowments granted controversial Sheikh Yasser Borhami, vice president of the Salafist Call, a preaching permit for Friday sermons in Alexandria in August, which sparked controversy and criticism in light of President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi's call for renewing religious discourse.

Egypt’s Ministry of Religious Endowments granted on Aug. 7, for the first time since 2014, Vice President of the Salafist Call Sheikh Yasser Borhami a preaching permit for Friday sermons between Aug. 1 and Aug. 31 at Al-Kholafaa Al-Rashdeen Mosque in Alexandria.

Borhami has repeatedly sparked controversy in the past with the fatwas he issues, including one barring Muslims from sending holiday greetings to Coptic Christians, another banning people from watching soccer games and one forbidding children from decorating their bedrooms with Disney character posters.

The Ministry of Religious Endowments issued a law in June 2014, according to which only imams who are graduates of Al-Azhar University are authorized to preach, and only after passing an interview with the nationwide endowments directorates affiliated with the ministry, which in turn issue the preaching permits.

The permit granted to Borhami includes seven instructions he must follow: First, he must abide by the unified sermon imposed by the Ministry of Religious Endowments, as per its July 2014 decision. Also, Borhami must abide by the Ash’ari doctrine, a moderate Islamic school of thought adopted by Al-Azhar. Second, his sermon must not exceed 15-20 minutes.

Borhami must not address any political or controversial issue in his sermon and no fatwas shall be pronounced in mosques. In addition, no religious lessons shall be given other than the Friday sermon preapproved by the ministry. Borhami must abide by the instructions issued by the ministry. He is also not allowed to move from one mosque to another unless there is prior approval from the director of the endowments directorate, the director of the department of preaching permits at the ministry and the area inspector appointed by the ministry to monitor preaching across the country. Finally, the permit shall also be considered personal property and must be preserve

The return of Borhami to preaching has raised many questions and criticism from secular citizens in Egypt, such as intellectual Khaled Montaser, and from parliamentarians such as Nadia Henry. This is mainly because Borhami’s fatwas in the past promoted hostility toward Copts, and he has not apologized for them. Meanwhile, Samir Sabry, a prominent Egyptian lawyer, filed a complaint against Sheikh Mohammed Khashaba, undersecretary of the Ministry of Religious Endowments in Alexandria, who granted Borhami the preaching permit.

In this regard, Abdul Moneim Shahat, the spokesman of the Salafist Call, told Al-Monitor, “Borhami holds a bachelor’s degree in Islamic studies from Al-Azhar University, and he applied in this capacity for the preaching permit before the Ministry of Religious Endowments, not in his capacity as deputy head of the Salafist Call. The Ministry of Religious Endowments does not deal with organizations such as the Salafist Call, but deals with each person as an individual by assessing them to ensure they meet the conditions required to obtain a preaching permit.”

Shahat noted, “The new measure taken by the ministry now includes its instructions — which were repeatedly published before — in the permit. What I am not sure of is whether the ministry decided on generalizing this measure to all permits, or whether it was something specific to Sheikh Borhami. But the instructions are not new, and there are no specific instructions that were only formulated for Borhami.”

He added, “The existence of a peaceful Salafist movement that rejects bloodshed and respects the tacit understandings [reached] with non-Muslims is the first guarantee to curb the spread of violence and takfiri [extremist] orientations.”

The Salafist Call was founded in Egypt in 1977. At first, its activities were limited to social and preaching work, and it refused to participate in political life. Meanwhile, the security forces were lenient toward the Salafist Call, compared to other Islamist movements, because it [the Salafist Call] did not seek to reach power and its presence undermined the Muslim Brotherhood’s monopolization of the Islamist current in the country.

But after the January 25 Revolution the situation changed. The Salafist Call formed its political wing, the Nour Party, which won 112 out of 508 seats in parliament in the 2012 legislative elections. After June 30, 2013, the movement faced increasing calls to dissolve it under the pretext that it is a religious party despite supporting the revolution. The army, however, rejected those calls as the dissolution of the Salafist Call would have changed the balance of power among Islamist currents. And thus, although the Salafist Call still enjoys political support, it came under harsh media campaigns, and ultimately faced a setback in the 2015 parliamentary elections, winning only 12 seats out of 596.

Ahmed Karima, a professor of comparative jurisprudence at Al-Azhar University, told Al-Monitor, “I feel that Salafism is being swept out of Saudi Arabia to be settled in Egypt with the help of international parties and forces that do not want stability in Egypt. And while Al-Azhar University professors are not allowed to speak out and preach, Borhami, the author of radical fatwas and patron of Salafism in Egypt, is granted this permit.”

Often professors who oppose the current regime in Egypt do not receive their preaching permits from the Ministry of Religious Endowments despite meeting the conditions.

There is a tendency today to get rid of Salafism in Saudi Arabia. Several Salafist preachers, fearing the campaigns led by Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, have fled to Egypt and settled mainly in Alexandria, the stronghold of Salafism in Egypt.

Karima added, “Salafists led by Borhami consider all Muslims [Sufis and Shiites] who do not adhere to their ideology as apostates, and accuse Al-Azhar of corrupt beliefs for following Ash'ari doctrine. Salafism spread in Egypt through Gulf funds and the movement managed to create bases for extremist thought through [media] channels. For example, Sheikh Mohammed Hassan — a leading Salafist preacher — is building a 30-acre Islamic complex in 6th of October City, with nurseries to teach children the principles of Salafism. Salafism is not a threat to Al-Azhar, but a threat to Islam.”

Secretary of the parliamentary Religious Committee Amr Hamroush told Al-Monitor, “I strongly condemn the recent decision by the Ministry of Religious Endowments to grant a preaching permit to Borhami — even if such permit was for a month or subject to restrictions — because this man did not apologize for past extremist fatwas. Borhami’s thoughts have not changed, even if he pretends to abide by the provisions of the Ministry of Religious Endowments to be able to preach. Therefore, I ask the ministry to reconsider this permit and withdraw it.”

Comments