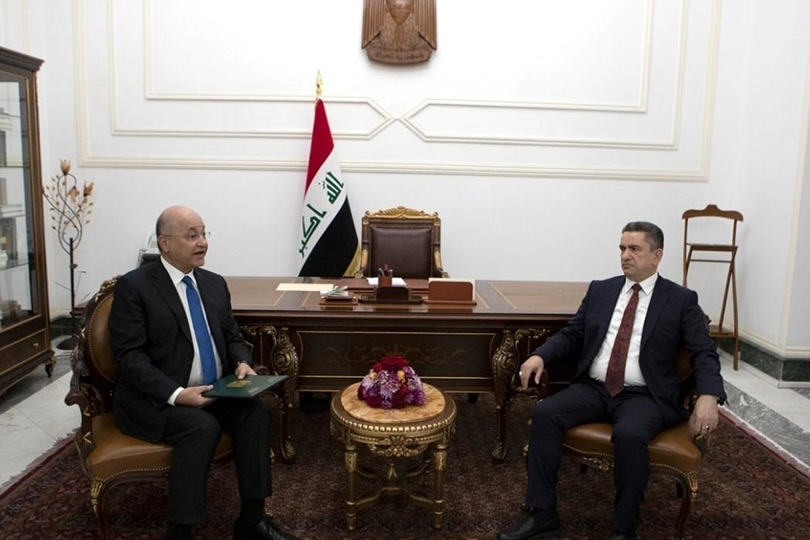

Iraq has a new prime minister-designate, almost three weeks after the previous nominee — Mohammed Tawfiq Allawi — failed to secure parliamentary approval for his cabinet. The new figure, Adnan al-Zurfi, is a veteran of the Iraqi opposition and a long-time member of the ruling class who worked closely with the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) during the U.S. occupation of Iraq.

A stern personality, he has a checkered and violent history with many of the people and groups with which the U.S. is currently clashing, including Muqtada al-Sadr (who has threatened to force the U.S. out of Iraq) and some members of the Iran-aligned leadership of the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), whose militias have struck U.S. bases in Iraq these past few weeks. These groups have already derided his nomination and will attempt to torpedo his efforts to form a government.

THE POLITICAL SCENE

The challenge facing al-Zurfi is twofold.

First, Iraq has been pushed to the brink by protests demanding reform since October, resulting in the deaths of hundreds and injuries to thousands as state-aligned security forces and militia groups loyal to Iran responded violently. The impact of the protests has been cataclysmic, plunging Iraq into its worst crisis since the Islamic State seized Mosul in 2014, while also rocking the political class to its core.

Second, to compound the crisis, Iraq has been hit with the rapid decline in oil prices and the coronavirus pandemic. Yet, protesters are still determined to force the political class from power and have criticized Iran-aligned groups that are now more determined than ever to dominate the political landscape and consolidate their hold on the Iraqi state, especially since the U.S. assassination of Iranian commander Qassem Soleimani in January.

The odds are stacked against the protesters. The political system and the dominant political order that has emerged since 2003 is impervious to long-term, wholesale changes. There is a strong, unwritten understanding among the ruling elites that commits them to maintaining an equilibrium of power in Iraq that satisfies the interests of the competing blocs, based on the premise that no single actor can or should monopolize power. It is also based on the premise that their hold on power, access to resources, and overall survival is underpinned by their own interdependence.

This has underpinned power structures in Iraq since 2003 and has been reinforced in every election since 2005: No single party or bloc has been able to win a plurality, rendering it necessary to form coalitions that secure the vested interests of rival blocs. In other words, even if al-Zurfi was able to form a government that was amenable to the protest movement — one comprised of independents for example — it would likely be torpedoed by the ruling class and fail to acquire parliamentary approval.

Conversely, a government that does placate the ruling class could end up being challenged by the protesters, and it may even revive the movement after it was stunted in recent weeks by the coronavirus crisis. Iraq may consequently be stuck in a state of stalemate for months, if not years. In that case, the current caretaker government led by Adel Abdul Mahdi may continue in its current capacity until elections can realistically take place.

A ROLE FOR WASHINGTON

In theory, the United States should back the protest movement and push for a wholesale reform of the Iraqi state that results in better governance, stronger sovereignty, and more jobs for the Iraqi population. In reality, however, that is very unrealistic for the foreseeable future.

The problem does not come down to any single individual or party. In some sense, it is immaterial whether al-Zurfi becomes prime minister, because of the multi-layered dynamics of power and governance that underpin the Iraqi state and political system. Iraq has formal authorities like the government, the parliament, and the judiciary; those often compete with informal authorities like militias, tribes, and clerical figures (some of whom control or dominate formal decision making structures) that have outsized influence over Iraq’s politics and economy.

There have been openings for the U.S. to swiftly move into the fray and enact measures that could decisively shift the political environment so that it is more conducive to securing viable and sovereign Iraqi institutions. For example, the assassination of Qassem Soleimani in January diminished Iran-aligned militias’ aura of invincibility and triggered a leadership crisis within their ranks that has weakened their grip in the country. That opened a temporary window of opportunity, had Washington followed it with an expansive political strategy focused on working with its allies and protecting them from Iran-aligned militias amid the ensuing volatile political environment. In the absence of U.S. support, few in Iraq were willing to move against a bruised but not bloodied Iran that was determined to maintain its influence in the country.

Such an approach could have secured vital U.S. interests in the near term (maintaining the U.S. troop presence in Iraq or mobilizing and supporting U.S. allies to reinforce the pushback against Iran’s influence). It would have been especially effective if it were combined with red lines, essentially threatening further military action against Iran’s proxies to secure long-term political objectives (reforming Iraq’s institutions, as well as mobilizing international investment and resources and the reconstruction of war-torn areas).

Al-Zurfi’s appointment might end the political paralysis in the country (assuming he can secure the backing of the most powerful parliamentary blocs). Were that to materialize, it would pave the way for a political process that is fraught with spoilers and structural issues that suppress the state’s ability to govern sustainably. In order to be a constructive partner to Iraq, Washington should identify steps it would like to see, recognizing the realities of governance and power in Iraq (that are abundantly clear to decisionmakers in Washington).

The U.S. is committed to undermining Iran’s proxies as part of its maximum pressure campaign against Iran. But the notion of dislodging Iran’s Iraqi proxies from power in Baghdad is implausible. These groups are too entrenched in local decisionmaking structures, too resource-rich, and too powerful having exploited U.S. myopia in Iraq ever since its 2011 withdrawal of forces. While U.S. sanctions have had economic consequences for Iran and its proxies, the U.S. has very little to show by way of a viable strategy that looks to reduce these groups’ grip on the levers of power, much less support the groups that have long sought to contest Iran’s influence in concert with the U.S.

EYE ON THE (COMMON) PRIZE

Iraq is engulfed in interconnected crises: a protest movement that has resulted in clashes and that could trigger either a violent rebellion or a full-scale massacre of civilians; U.S.-Iran tensions that might result in a war on Iraqi soil; and a political crisis that could pave the way for conflict between rival factions.

Much of the heavy lifting has to be done by Iraqis themselves, but the U.S. must also re-evaluate its position and build on its commitment to defeat ISIS by helping to develop a vision for Iraq’s future based on the facts on the ground. Ideally, the U.S. and key U.S. allies in Iraq would outline a political strategy for a full-spectrum response to the array of challenges Iraq faces, one that secures vital strategic interests at the same time. Currently, the most salient contributions from the U.S. are its military and technical support — which has prevented an ISIS resurgence — and its retaliatory attacks on Iran’s proxies. Important as these may be, the U.S. risks being perceived as a spoiler and disruptor among a population that is yearning for outside assistance — assistance that helps Iraqis achieve better governance, a revived economy, and a balanced foreign policy.

Comments