The Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) was the law that prosecutors deployed against Aaron Swartz, an internet activist who killed himself after a years-long legal battle centered around his decision to mass download academic journals. On April 13, the CFAA was used to sentence Matthew Keys, a former LA Times employee accused of giving a username and password to a hacker who defaced an article, to two years in prison.

“The problem is [the CFAA] is so broadly written, and it fails to define what it seeks to prohibit,” Keys’ lawyer, Tor Ekeland, who plans on appealing, tells Newsweek.

Keys was convicted of giving the hacker collective Anonymous access to his old employers’ servers and telling them to “go fuck some shit up.” One of them did just that, and an article on the LA Times website was vandalized and stayed live for about 40 minutes before the paper’s staff fixed it. Keys still denies involvement.

Keys faced up to 25 years under the CFAA. “That seems disproportionate to me. It’s a silly prank that really didn’t harm anybody. This prosecution is a little over the top,” Ekeland says.

The CFAA makes it a federal crime to access a “protected computer,” but says the law only applies if the “value of such use” is $5,000, or if the person accessing the protected computer causes more than $5,000 in damage. But when the damage is data, or the cost of repairing a system, that number can be very hard to calculate. Early on, prosecutors put the damage of the LA Times vandalism, and the cost of responding to some harassing spam email messages they allege Keys sent, at $900,000—the court finally accepted damages of $18,000. Ekeland argues the damages are even lower and should be below the law’s threshold.

The CFAA actually predates the internet as most of us know it. In 1986, most Americans had never seen a computer, let alone used one. Likely, their idea of hacking was something like what they saw in the movie War Games—a kid almost causing a nuclear war with his computer and a phone line. Congress passed the law before hacking crimes really existed. It’s telling that the law specifically excludes “a portable hand held calculator.”

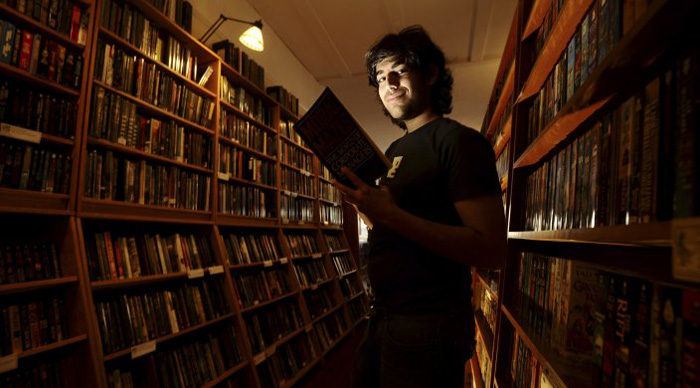

The broad definition and high penalties have made the law a go-to option for prosecutors in computer cases where both the crime and the perceived losses are hard to explain. Swartz was hit with the law after he entered a network closet at MIT and mass downloaded millions of academic journals from JSTOR, a company that generally charges for access. Swartz was charged with essentially violating the terms of service of JSTOR; because the CFAA was applied, he faced years in prison. Swartz ultimately killed himself after a plea deal was rejected by prosecutors.

After Swartz’s death a bill to change the law so it wouldn’t apply to simply violating the terms of service was introduced to Congress. As lawyer and Swartz supporter Lawrence Lessig wrote, “no longer would it be a felony to breach a contract.”

The amendment ultimately failed but even if it passed, it would have left the core of the law, which doesn’t define damages or unauthorized access, unchanged. Keys wrote an essay saying that the application of the law could apply to anyone who shared a Netflix password, for instance, although in that case the company would also have to prove $5,000 in losses.

The law “criminalizes normal computer usage engaged in Americans every single day,” Ekeland says. “The government’s response to this is ‘just trust us,’ but as soon as they see somebody’s speech they don’t like, they go after them.” One of Ekeland’s previous clients was a notorious internet troll who harvested email addresses from a badly programmed form on a login page of a company website and was convicted under CFAA. His conviction was eventually overturned.

It’s not just defense attorneys who have trouble with the law. Security professionals say CFAA hurts their quest of making the internet safe. Alex Rice is the CTO at HackerOne, a company that runs “bug bounty” programs to help companies find security holes in their products. Rice says CFAA is a constant threat in his profession.

At an earlier job Rice would monitor companies, and if their servers were compromised and being used by malicious hackers, he’d get in touch with them to let them know. He says often the response would be a cease-and-desist letter citing the CFAA. Just confirming that a remote server has been taken over could qualify as a violation of the law, according to Rice—or it might not. But it’s basically impossible to know. “CFAA was drafted at a time when the internet didn’t really exist and has been applied so inconsistently it’s impossible to actually know if you’re in violation,” Rice says. The result is companies can often scare well-meaning security professionals away from doing their jobs.

HackerOne tries to address the problem with clear rules for things their hired hackers can do on client company servers without incurring legal problems. Even then, it doesn’t mean that security professionals are exempt from the law, only that the companies won’t pursue legal action. The client company making that statement can’t actually give white hat hackers immunity to the law itself, but the system works because it’s incredibly rare for the U.S. to prosecute someone without a victim.

Another security professional, Casey Ellis, the CEO and founder of Bugcrowd, says conflicts with the CFAA are avoidable, as long as security professionals are getting sign-offs, permissions and rules of engagement from the companies they work with. He also think it’s important that companies have legal rights when they’ve been attacked. “The LA Times should be able to defend and pursue this type of behavior, but the sentencing that has been discussed along the way is without precedent, and speaks to the broadness of the act,” Ellis writes to Newsweek.

The CFAA doesn’t show any signs of going anywhere. Just last year the Obama administration proposed changes that would “ensur(e) that insignificant conduct does not fall within the scope of the statute,” but in actuality broadened the law, according to experts.

Comments