JOSCHKA FISCHER

On May 16, 1916, in the middle of World War I, Great Britain and France signed a secret pact in London. Officially known as the Asia Minor Agreement, the deal, negotiated by the diplomats Mark Sykes and François Georges-Picot, has determined the fate and political order of the Middle East ever since. But not for much longer.

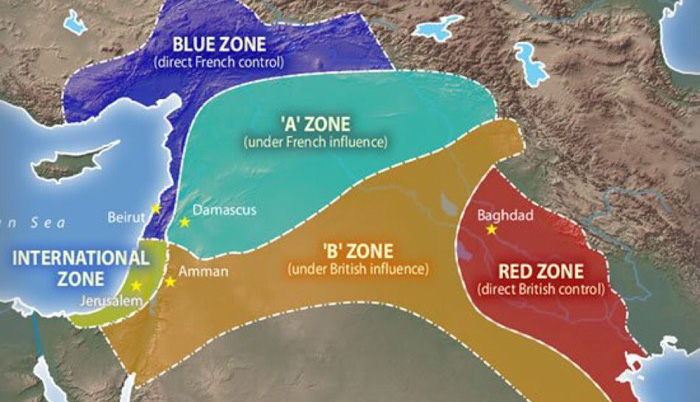

A century ago, Europe’s soon-to-be-victorious powers, concerned with dividing the region (then part of the Ottoman Empire), drew a “line in the sand” (as the author James Barr called it) stretching from the Mediterranean port of Acre in northern Palestine to Kirkuk in northern Iraq, on the border with Iran. All territories north of that line, in particular Lebanon and Syria, would go to France. Territories to its south – Palestine, Transjordan, and Iraq – would go to Great Britain, which mainly sought to protect British interests along the Suez Canal, the main naval route to British India.

Simultaneously, however, the United Kingdom was negotiating with Arabs who had sided with the British and French in an uprising against Ottoman rule – first and foremost with Hussein bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca. Hussein had been promised Syria in the event of a military victory over the Turks. But under the Sykes-Picot agreement, Syria had been awarded to France. So one of the two sides was certain to be cheated out of the spoils of its victory, and it was clear from the beginning which side was weaker, namely the Arabs striving for independence.

The secret agreement negotiated by Sykes and Picot subsequently led to the formation of states that served the great European colonial powers’ geopolitical interests, not the social, religious, and ethnic realities of the region. A political order was forced upon the Muslim Middle East by Christian European powers that had flouted their commitments to Arab independence – an order that has been at the root of a century of war and conflict.

In the Arab world, the trauma of that betrayal and the defeat of the national movement has lingered. But Sykes and Picot did bring about a reconciliation between the two great Entente powers, and the regional order they created in the aftermath of centuries of Turkish/Ottoman rule endured. The European hegemons, Britain and France, took the place of the Sublime Porte, guaranteeing this order either directly or via regional proxies.

After World War II, the United States assumed the role of ultimate guarantor of the Sykes-Picot system. But America’s experience in Iraq following its 2003 intervention, and spreading turmoil there and elsewhere, led the US to withdraw its forces and reduce its involvement in the region. With that, the Sykes-Picot system began to collapse.

That is why today’s main crises in the Middle East are playing out precisely in the heartland of the Sykes-Picot Agreement: Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq. The “Kurdish question,” too, has returned to the fore.

Only Israel and Jordan seem to be stable – with an emphasis on “seem.” Without reconciliation between Israelis and Palestinians, it is only a matter of time before the Palestinian powder keg ignites once again. And Jordan’s stability rests largely on the loyalty of the army and the Bedouin tribes to the monarchy, as well as a highly efficient secret service. But these are insufficient bases of resilience, particularly given the tectonic shifts occurring next door, in Iraq and Syria.

Those two countries are now the main theaters in the battle for a post-Sykes-Picot Middle East order. Both had been unstable for a long time, ruled by secular Ba’athist dictators who faced popular majorities that adhered to a rival Muslim sect, in addition to a large population of Kurds, who have long dreamed of independence.

The post-Sykes-Picot order will be the result of fighting in the coming years between regional powers – first and foremost Iran and Saudi Arabia – and their religiously motivated auxiliaries, such as the Shia Hezbollah or the Sunni Islamic State. Any Western military intervention would only exacerbate the situation.

The era when a Western hegemon could maintain control of the Middle East, by military force if necessary, is over. Regional forces, not external powers (including Russia), will create the new order in the Middle East emerging out of the remains of the Sykes-Picot system. By the time proxy wars like the one in Syria have finished their work, the Sykes-Picot Agreement will be history.

But the new order could be slow to emerge, because none of the region’s powers is strong enough to impose its will on the others. Should they opt for a useless struggle for hegemony, the Middle East will face a major political and humanitarian calamity. In the end, total exhaustion on all sides will force reconciliation and the first steps in the direction of a regional peace settlement.

One thing is clear: The longer the breakthrough to a new order takes, the worse off everyone will be. A prolonged process and period of balkanization in the Middle East would result in nothing but more misery and suffering – constituting an enormous ticking time bomb for world peace. For those outside the region, the only hope is that no one within it can have a serious interest in that.

* Joschka Fischer was German Foreign Minister and Vice Chancellor from 1998-2005.

Comments