After a year of death, despair, and deep uncertainty, there are glimmers of light on the horizon. Not only is responsible leadership returning to the United States, but there is new momentum behind efforts to address some of the biggest and most urgent challenges of our time.

A lot of chickens came home to roost this year. The COVID-19 pandemic was not some random thunderbolt from out of the blue, but rather a man-made “natural” disaster, holding up a mirror to so many of our bad habits and dangerous – indeed, lethal – practices.

After all, the coronavirus’s transmission from bats to humans was a product of mass urbanization and destructive encroachment on natural habitats, and its rapid spread was a result of over-industrialization, frenetic trade, and contemporary travel habits. Likewise, the world’s inability to come together to contain the crisis reflects the extent to which governance capacity lags behind hyper-globalization.

Many of these failings were evident before the virus hit, with people in many countries embracing nationalist and populist leaders who promised decisive action in a world that seemed out of control. But though this has been a difficult year, there are at least five reasons to be cheerful about 2021.

The first and most obvious reason is US President Donald Trump’s defeat. It is a relief to be able to wake up in the morning without worrying about what the world’s most powerful person said on Twitter while you were sleeping. The United States will soon be back in capable hands. In addition to making America more predictable and responsible, President-elect Joe Biden’s victory holds important implications for democracies around the world.

Europe’s own Trumpians – Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and Poland’s deputy prime minister and de facto ruler, Jarosław Kaczyński – have already been orphaned by Trump’s political demise. As Europeans look ahead to their own elections – in the Netherlands and Germany in 2021, and in France in 2022 – populist parties will have less claim to be channeling the tide of history. In the United Kingdom, Prime Minister Boris Johnson – a consummate political weathervane – is already shifting with the new political winds. Following Trump’s loss, he finally fired his populist Brexit guru, Dominic Cummings, and signaled that he would be crafting a new identity for the post-Trump world.

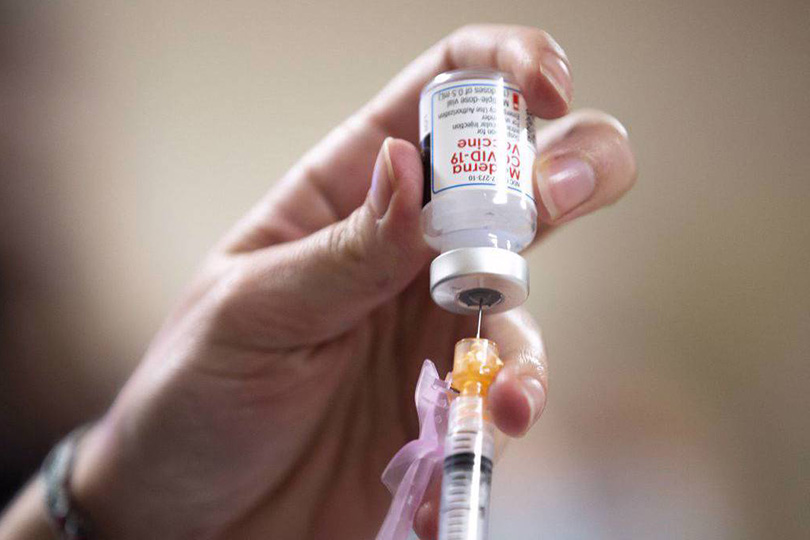

The second reason to be cheerful is that COVID-19 vaccines are on the way. This will allow for a gradual return to normality, and the way they were developed should reaffirm our support for international cooperation. It was nothing if not inspiring to see the first vaccine come from BioNTech, a European Union-funded company led by two German scientists of Turkish descent. Given justifiable concerns about “vaccine nationalism,” it is important that the people have seen that internationalism, not parochialism, is the path out of this and other global crises.

That brings me to the third reason for optimism: encouraging news on the climate front. As many commentators have noted, climate change could lead to an even bigger crisis than COVID-19. But following a massive 7% decline in greenhouse-gas emissions this year, we at least know what is possible. And now that governments have proved capable of spending whatever it takes in an emergency, they will face growing pressure to invest in the technologies needed for a rapid transition to clean energy.

The fourth cause for cheer is the return of faith in government. COVID-19 has reminded everyone just how valuable competent public administration can be. It also has brought new attention to the need for redistribution. After the 2008 financial crisis, many hoped that the prevailing neoliberal orthodoxy would give way to social democracy and greater political control over the economy. Instead, we got bank bailouts and other glaring examples of “socialism for the rich and capitalism for the poor.”

After a decade of painful austerity and the political upheavals it caused, governments are finally taking more responsibility for public welfare. Mainstream parties, including the Democrats in the US, are pushing policies to support workers and the middle class, offering hope that structural inequality, which leaves many feeling “left behind” (and thus open to populist appeals), will finally be addressed.

That brings us to the last reason to be cheerful. The pandemic has triggered a reconsideration of the global system. In place of unregulated hyper-globalization, many leading powers are looking for ways to reconcile the appetite for cheap goods, advanced technologies, and other benefits of trade with greater control over domestic affairs. Whether it is talk of “decoupling” in the US, “dual circulation” in China, or “strategic autonomy” in Europe, long-overdue policy debates are now underway.

Here, I find the European conversation particularly heartening, since it is focused on channeling the desire for more control in ways that preclude self-defeating nationalism. The EU’s quest for sovereignty spans at least five areas (economic and financial issues, public health, digitalization, climate policy, and security), and Europeans have been making good progress in all of them. The creation of a €750 billion ($915 billion) recovery fund shows that countries like Germany are willing to cross their traditional red lines in the interest of solidarity.

Of course, it is too early to declare victory in any of our current battles. Biden will struggle to govern a polarized country in the face of Republican resistance. Delivering vaccines to the entire world will be an enormous logistical challenge. Competing great powers could yet derail the climate agenda in the lead-up to the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow in November. The threat of recession and new debt crises could exacerbate inequality, auguring a return to more toxic politics. The revival of the European dream will depend on the outcome of highly contested national elections.

But as 2021 nears, things look a lot better than they did just a few months ago. We now have at least five reasons to celebrate the New Year.

Comments