Ilan I. Berman

National security adviser John Bolton traveled to Israel this month to reassure jittery officials in Jerusalem that the Trump administration isn’t planning a precipitous exit from Syria, notwithstanding the president’s surprise December announcement to the contrary. But Mr. Bolton’s most important message might have had nothing to do with America’s commitment to fighting Islamic State or its efforts to roll back Iran’s strategic influence in Syria and Iraq. The Trump administration, Mr. Bolton told Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, is concerned about the commercial relationship between Israel and China—and the strategic vulnerabilities those ties have created.

The most immediate worry is China’s impending access to Israel’s strategic northern port of Haifa. In 2015 China’s Shanghai International Port Group signed a multibillion-dollar deal with the Israeli Transportation Ministry for the future rights to operate the Haifa port. Under the terms of the agreement, the Chinese company will take control of day-to-day operations at the port for 25 years beginning in 2021.

Haifa isn’t only a commercial hub but a fixture in the long-running American-Israeli strategic partnership. It regularly hosts naval visits from the U.S. Sixth Fleet and joint naval exercises between the two countries. U.S. military officials therefore warn that port visits could be scaled back or even terminated once China assumes control of the facility in 2021.

Israel’s emerging China problem is bigger than Haifa. U.S. officials are also carefully watching China’s increasing penetration of Israel’s vibrant high-tech sector. After years of systematic investments, the Chinese may now directly control or have influence over as much as 25% of Israel’s tech industry. The U.S. wants to strengthen Israeli control of China’s growing economic sway in the country.

When a foreign nation wants to make a substantial investment in a sensitive sector of the American economy, it is reviewed by an interagency body known as the Committee on Foreign Investment in the U.S. Cfius has the authority to nix deals that could have an adverse impact on national security. But Cfius has no Israeli analogue; the Israeli government’s decisions about foreign investment are too often driven more by economic than security considerations.

This approach might be viable if Israel were a minor country disconnected from great-power politics. But Israel’s vital geostrategic location, sophisticated military and technology sector, and deep ties to the U.S. make its lack of a formal foreign-investment oversight body untenable over the long run.

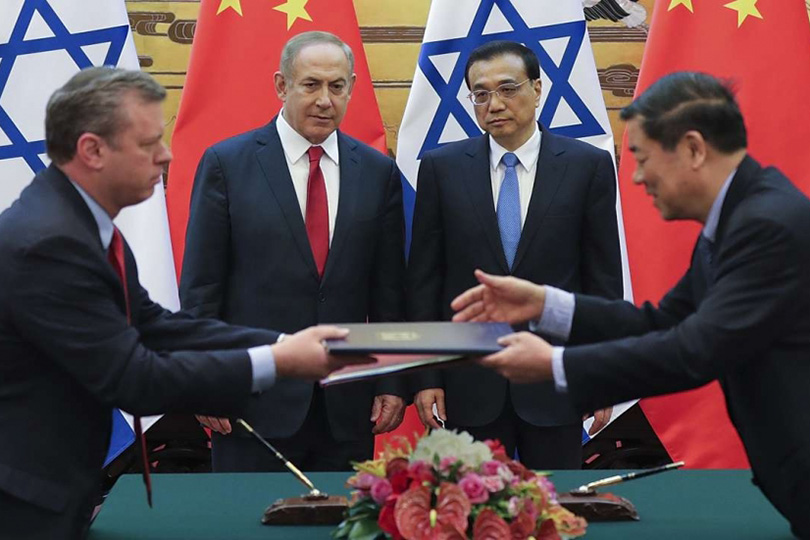

In its eagerness to live up to its reputation as a global commercial and innovation hub, Israel has engaged deeply with China, potentially damaging its strategic relationship with the U.S. Mr. Bolton was right to deliver a stern message during his recent visit. Fortunately, Jerusalem seems to have received and understood it. Senior Israeli statesmen, including the country’s former ambassador to China, have called for a “rethink” of the Haifa port deal, and the Netanyahu government seems inclined to do it.

Still, the larger risks associated with China’s growing investments in the Jewish state, and their implications for Israel’s security as well as its relations with key international partners, haven’t been sufficiently addressed by policy makers in Jerusalem. They should be, and soon. The long-term dynamism of the U.S.-Israeli strategic partnership could depend on it.

Comments