Kenneth Rogoff

The debate about how to regulate the tech sector is eerily reminiscent of the debate over financial regulation in the early 2000s. Fortunately, one US politician has mustered the courage to call for a total rethink of America's exceptionally permissive merger and acquisition policy over the past four decades.

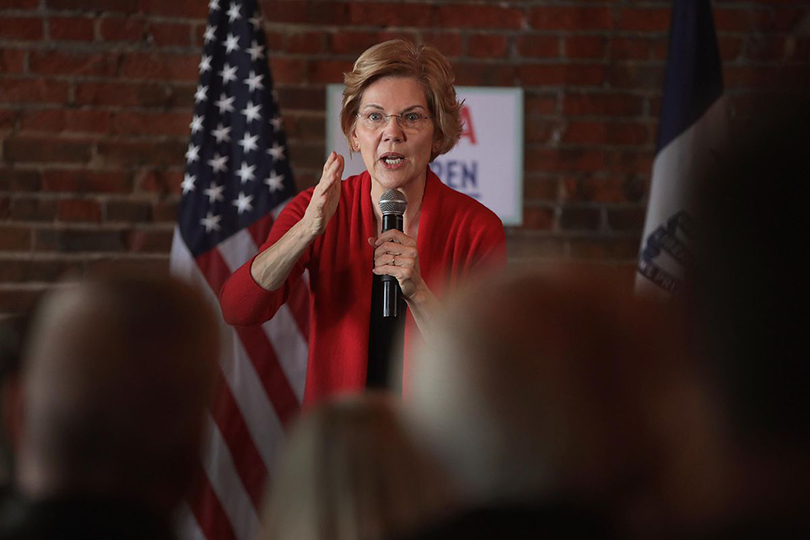

Displaying a degree of courage and clarity that is difficult to overstate, US senator and presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren has taken on Big Tech, including Facebook, Google, Amazon, and Apple. Warren’s proposals amount to a total rethink of the United States’ exceptionally permissive merger and acquisition policy over the past four decades. Indeed, Big Tech is only the poster child for a significant increase in monopoly and oligopoly power across a broad swath of the American economy. Although the best approach is still far from clear, I could not agree more that something needs to done, especially when it comes to Big Tech’s ability to buy out potential competitors and use their platform dominance to move into other lines of business.

Warren is courageous because Big Tech is big money for most leading Democratic candidates, particularly progressives, for whom California is a veritable campaign-financing ATM. And although one can certainly object, Warren is not alone in thinking that the tech giants have gained excessive market dominance; in fact, it is one of the few issues in Washington on which there is some semblance of agreement. Other candidates, most notably Senator Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota, have also taken principled stands.

Although the causal relationships are difficult to untangle, there are solid grounds for believing that the rise in monopoly power has played a role in exacerbating income inequality, weakening workers’ bargaining power, and slowing the rate of innovation. And, perhaps outside of China, it is a global problem, because US tech monopolies have often achieved market dominance before local regulators and politicians know what has happened. The European Union, in particular, has been trying to steer its own course on technology regulation. Recently, the United Kingdom commissioned an expert group, chaired by former President Barack Obama’s chief economist (and now my colleague) Jason Furman, that produced a very useful report on approaches to the tech sector.

The debate about how to regulate the sector is eerily reminiscent of the debate over financial regulation in the early 2000s. Proponents of a light regulatory touch argued that finance was too complicated for regulators to keep up with innovation, and that derivatives trading allows banks to make wholesale changes to their risk profile in the blink of an eye. And the financial industry put its money where its mouth was, paying salaries so much higher than those in the public sector that any research assistant the Federal Reserve System trained to work on financial issues would be enticed with offers exceeding what their boss’s boss was earning.

There will be similar problems staffing tech regulatory offices and antitrust legal divisions if the push for tighter regulation gains traction. To succeed, political leaders need to be focused and determined, and not easily bought. One only has to recall the 2008 financial crisis and its painful aftermath to comprehend what can happen when a sector becomes too politically influential. And the US and world economy are, if anything, even more vulnerable to Big Tech than to the financial sector, owing both to cyber aggression and vulnerabilities in social media that can pervert political debate.

Another parallel with the financial sector is the outsize role of US regulators. As with US foreign policy, when they sneeze, the entire world can catch a cold. The 2008 financial crisis was sparked by vulnerabilities in the US and the United Kingdom, but quickly went global. A US-based cyber crisis could easily do the same. This creates an “externality,” or global commons problem, because US regulators allow risks to build up in the system without adequately considering international implications.

It is a problem that cannot be overcome without addressing fundamental questions about the role of the state, privacy, and how US firms can compete globally against China, where the government is using domestic tech companies to collect data on its citizens at an exponential pace. And yet many would prefer to avoid them.

That’s why there has been fierce pushback against Warren for daring to suggest that even if many services seem to be provided for free, there might still be something wrong. There was the same kind of pushback from the financial sector fifteen years ago, and from the railroads back in the late 1800s. Writing in the March 1881 issue of The Atlantic, the progressive activist Henry Demarest Lloyd warned that,

“Our treatment of ‘the railroad problem’ will show the quality and caliber of our political sense. It will go far in foreshadowing the future lines of our social and political growth. It may indicate whether the American democracy, like all the democratic experiments which have preceded it, is to become extinct because the people had not wit enough or virtue enough to make the common good supreme.”

Lloyd’s words still ring true today. At this point, ideas for regulating Big Tech are just sketches, and of course more serious analysis is warranted. An open, informed discussion that is not squelched by lobbying dollars is a national imperative. The debate that Warren has joined is not about whether to establish socialism. It is about making capitalist competition fairer and, ultimately, stronger.

Comments