In 2013, Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg released a 10-page white paper outlining his new vision, titled “Is Connectivity a Human Right?”. It contained “a rough proposal for how we can connect the next five billion people”, with help from a consortium of tech companies christened Internet.org. Not only did Zuckerberg’s plan include broadening access to existing telecommunications networks, it even covered developing new technologies like solar-powered drones that would loiter over remote areas, beaming data connections to the people below.

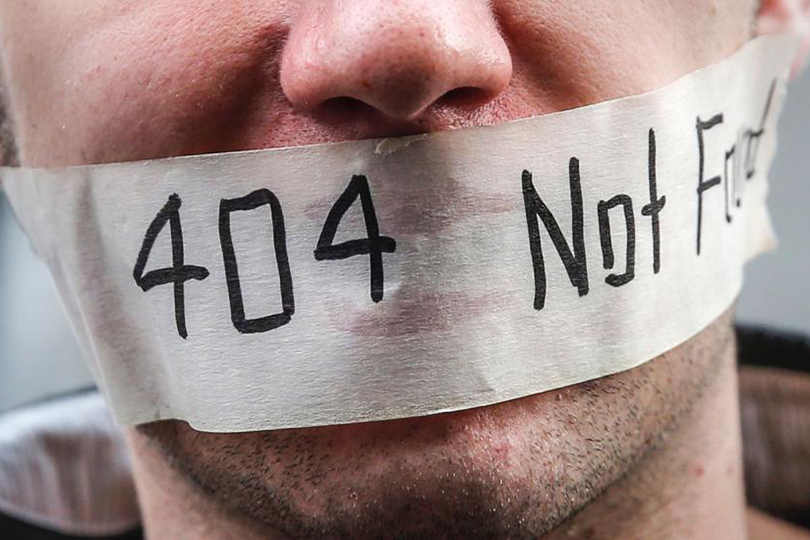

Half the world’s population lives without a reliable internet connection, which limits their access to education, financial services, political engagement, free expression, and more. Among them is Salim Azim Assani, co-founder of WenakLabs, a digital hub in N’Djamena, the capital of Chad. In 2008, government authorities shut down access to social media like Facebook and Twitter, citing the spread of religious extremism. The services remained offline for 16 months.

“We lost money, and some of our customers, because of the internet block,” says Assani. “Some of our customers cancelled their contracts because they think it is not a good moment to use social media. Working with artists or musicians, they can’t have a lot of views because a lot of people don’t know how to use VPNs, or because VPNs are not easy for them to use.”

Fifty years after the first computers were laced into an internet, and 30 years since the World Wide Web was built on top of this “network of networks”, the free and open online world envisioned by early pioneers is under attack. In the last few years, partial cuts and even total blackouts have been reported in India, Sudan, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Syria, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Iraq.

Joshua Franco is deputy director of Amnesty Tech. While the organisation doesn’t comprehensively monitor the world for internet shutdowns, he says the practice is increasing. “In the west and central Africa region we found 12 cases of intentional mobile and internet cuts in 2017, up from 11 in 2016. In 2018, we had 20 in that region,” he says. “Our fear is that would continue to rise.”

Typically, the justification for these cuts is to curb unrest: when Sri Lankan authorities cut access to social media in the wake of the 2019 Easter terror attacks, they said this was necessary to prevent the spread of misinformation and panic. “We look more at impact, because the motives are not always totally knowable,” says Franco. But he adds: “The coincidence around crucial public events, such as elections and protests, raise our suspicions that it’s a way of quelling free speech.”

Taking the internet offline is a crude measure, but other methods of shaping internet access can be just as dramatic. The Russian government, for example, is building a parallel internet that exists entirely within its own borders. Once complete, this will give the Russian authorities complete control over what users based in Russia can see and post online. And internet users in mainland China log on to one of the most heavily regulated online spaces in the world, where restrictions to foreign websites and services, active filtering of offending content and strict legal provisions for companies operating online combine in what is known as "The Great Firewall of China".

And the trend continues even in more liberal nations. A copyright directive passed by the EU this year, known as Article 13, compels web operators to install filters that will automatically remove content deemed illegal. In the UK, the government has repeatedly asserted that it should be allowed to break the encryption that underlies everything from private messaging apps to online payments. And in the US, lawmakers have repeatedly tried to overturn net neutrality rules that ensure online services are treated equally.

Young people have the right to open social media, to use the internet, and they have to use it to learn to do business – Salim Azim Assani

Two years after launching Internet.org, Zuckerberg appeared before the UN General Assembly to reiterate that “the internet belongs to everyone”. He’s not alone in this view: reports from the UN Human Rights Council in 2011 and 2016 criticised internet restrictions as running afoul of international agreements on freedom of expression and information. Both times, they were widely reported as being a declaration that internet access itself was a human right.

“The internet is a human right,” agrees Assani, who also runs a non-profit organisation dedicated to promoting digital services in Chad. “Young people have the right to open social media, to use the internet, and they have to use it to learn to do business. All people have the right to use the internet.”

Vint Cerf doesn’t agree. His opinion ought to count for something: as the co-developer of the TCP/IP protocol, he’s known as one of the “fathers of the internet”. Following the 2011 UN report, he wrote an editorial in the New York Times dismissing the notion that internet access was a human right.

Cerf posited that as a technology, the internet was an enabler of rights, and confusing the two would lead to us valuing the wrong things. “At one time if you didn’t have a horse it was hard to make a living,” Cerf wrote. “But the important right in that case was the right to make a living, not the right to a horse.” The internet was a means to an end, and not the end itself.

Behind the headlines, this is the position of the UN Human Rights Council as well. The reports issued in 2011 and 2016 highlighted the essential nature of the internet in enabling people to exercise their freedom of expression, opinion and information, but they stopped short of declaring access to a free and open internet a human right in itself.

Facebook community standards or company policies cannot replace the UN Declaration on Human Rights – Joshua Franco

Indeed, an internet that operates for the benefit of all necessarily comes with some restrictions. “It’s not illegal to restrict human rights in key situations,” says Franco. To spin a phrase, the right to free expression online doesn’t necessarily extend to shouting “fire” in a crowded chatroom.

For decades, regulators have been playing catch up with the web, introducing laws to curtail the spread of pirated music, drug selling, child pornography, terrorist propaganda, hate speech, and more. But the problem with a network of billions is that everyone has their own idea of what illegitimate content is. This isn’t just a discussion for different nations, but also for the services that operate online. “Facebook community standards or company policies cannot replace the UN Declaration on Human Rights,” says Franco.

Asserting our internet rights, then, means taking a proactive stance. The World Wide Web Foundation is a non-profit which aims to defend freedoms online. At the Internet Governance Forum in Berlin this November, it will launch its Contract for the Web. “It’s been really challenging for policy makers to come to terms with what is the web for,” says Emily Sharpe, policy director of the Web Foundation. “The Contract for the Web is about making sure the web is empowering and accessible to everyone.”

The document asserts the principles of a free, open, and inclusive web, and forms a manifesto for everyone aiming to make that vision a reality. Governments that sign up to the contract will pledge to connect everyone equally, keep the internet online, and respect citizens privacy. Companies can promise the same, as well as agreeing to develop technologies that “support the best in humanity and challenge the worst”. Individual citizens, too, can sign up and agree to create, collaborate, build communities and defend the online space.

In the six years since Zuckerberg launched Internet.org, progress to bring the world online has been faltering

“In the years since it was created, we’ve seen the web advance human rights,” says Sharpe. But she notes that as with most technologies, the initial enthusiasm surrounding the innovation often overlooks potential for damage that it can pose. She hopes that the contract will guide policy makers in creating regulations that balance the need to mitigate online harms with the fulfilment of human rights on the web.

“Concepts such as hate speech are frequently abused,” says Franco. “This is not to mean hate speech isn’t real – we’ve documented how violence against women drives them out of the public sphere and limits freedom of expression – but it is something governments seize on for those criticising them, and other forms of protected speech.”

In the six years since Zuckerberg launched Internet.org, progress to bring the world online has been faltering. Telecoms companies were reluctant to move people onto data plans where existing contracts for text messaging and voice calls were more profitable. And in 2018, Facebook quietly grounded its Aquila project for internet drones.

As such, there are still billions of people around the world who are not connected to the internet. But in our efforts to bring them online, we shouldn’t lose sight of what kind of internet we’re hoping to connect them to. It’s not enough to connect the world: we have to work hard to ensure that there is a web worth connecting to.

Comments