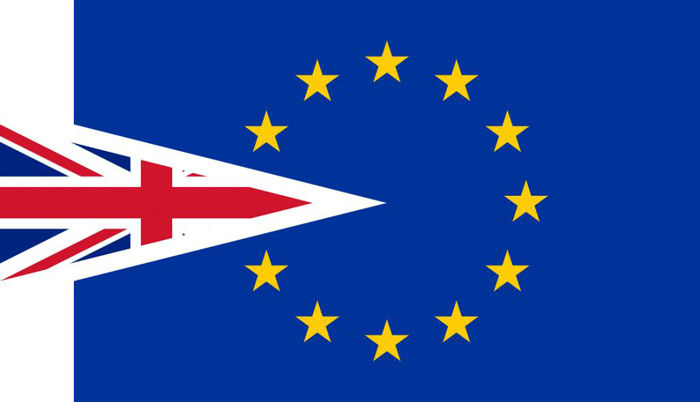

HOW quickly the unthinkable became the irreversible. A year ago few people imagined that the legions of Britons who love to whinge about the European Union—silly regulations, bloated budgets and pompous bureaucrats—would actually vote to leave the club of countries that buy nearly half of Britain’s exports. Yet, by the early hours of June 24th, it was clear that voters had ignored the warnings of economists, allies and their own government and, after more than four decades in the EU, were about to step boldly into the unknown. Managing the aftermath, which saw the country split by age, class and geography, will need political dexterity in the short run; in the long run it may require a redrawing of traditional political battle-lines and even subnational boundaries. There will be a long period of harmful uncertainty. Nobody knows when Britain will leave the EU or on what terms. But amid Brexiteers’ jubilation and Remain’s recriminations, two questions stand out: what does the vote mean for Britain and Europe? And what comes next?

Brexit: the small print

The vote to Leave amounts to an outpouring of fury against the “establishment”. Everyone from Barack Obama to the heads of NATO and the IMF urged Britons to embrace the EU. Their entreaties were spurned by voters who rejected not just their arguments but the value of “experts” in general. Large chunks of the British electorate that have borne the brunt of public-spending cuts and have failed to share in Britain’s prosperity are now in thrall to an angry populism.

Britons offered many reasons for rejecting the EU, from the democratic deficit in Brussels to the weakness of the euro-zone economies. But the deal-breaking feature of EU membership for Britain seemed to be the free movement of people. As the number of new arrivals has grown, immigration has risen up the list of voters’ concerns.

Accordingly, the Leave side promised supporters both a thriving economy and control over immigration. But Britons cannot have that outcome just by voting for it. If they want access to the EU’s single market and to enjoy the wealth it brings, they will have to accept free movement of people. If Britain rejects free movement, it will have to pay the price of being excluded from the single market. The country must pick between curbing migration and maximising wealth.

David Cameron is not the man to make that choice. Having recklessly called the referendum and led a failed campaign, he has shown catastrophic misjudgment and cannot credibly negotiate Britain’s departure. That should now fall to a new prime minister.

We believe that he or she should opt for a Norwegian-style deal that gives full access to the world’s biggest single market, but maintains the principle of the free movement of people. The reason is that this would maximise prosperity. And the supposed cost—migration—is actually beneficial, as Leave campaigners themselves have said. European migrants are net contributors to public finances, so they more than pay their way for their use of health and education services. Without migrants from the EU, schools, hospitals and industries such as farming and the building trade would be short of labour.

Preventing Frexit

The hard task will be telling Britons who voted to Leave that the free having and eating of cake is not an option. The new prime minister will face accusations of selling out—for the simple reason that he or she will indeed have to break a promise, whether over migration or the economy. That is why voters must confirm any deal, preferably in a general election rather than another referendum. This may be easier to win than seems possible today. While a deal is being done, the economy will suffer and immigration will fall of its own accord.

Brexit is also a grave blow for the EU. The high-priesthood in Brussels has lost touch with ordinary citizens—and not just in Britain. A recent survey for Pew Research found that in France, a founder member and long a strong supporter, only 38% of people still hold a favourable view of the EU, six points lower than in Britain. In none of the countries the survey looked at was there much support for transferring powers to Brussels.

Each country feels resentment in its own way. In Italy and Greece, where the economies are weak, they fume over German-imposed austerity. In France the EU is accused of being “ultra-liberal” (even as Britons condemn it for tying them up in red tape). In eastern Europe traditional nationalists blame the EU for imposing cosmopolitan values like gay marriage.

Although the EU needs to deal with popular anger, the remedy lies in boosting growth. Completing the single market in, say, digital services and capital markets would create jobs and prosperity. The euro zone needs stronger underpinnings, starting with a proper banking union. Acting on age-old talk of returning powers, including labour-market regulation, to national governments would show that the EU is not bent on acquiring power no matter what.

This newspaper sees much to lament in this vote—and a danger that Britain will become more closed, more isolated and less dynamic. It would be bad for everyone if Great Britain shrivelled into Little England and be worse still if this led to Little Europe. The leaders of Leave counter with the promise to unleash a vibrant, outward-looking 21st-century economy. We doubt that Brexit will achieve this, but nothing would make us happier than to be proved wrong.

The tumbling of the pound to 30-year lows offered a taste of what is to come. As confidence plunges, Britain may well dip into recession. A permanently less vibrant economy means fewer jobs, lower tax receipts and, eventually, extra austerity. The result will also shake a fragile world economy. Scots, most of whom voted to Remain, may now be keener to break free of the United Kingdom, as they nearly did in 2014. Across the Channel, Eurosceptics such as the French National Front will see Britain’s flounce-out as encouragement. The EU, an institution that has helped keep the peace in Europe for half a century, has suffered a grievous blow.

Comments