Almost a month ago, a brief note reached all Iraqi forces linked to Iran. The Islamic Republic, it said, was leaving Iraqi politics to the Iraqis.

"The Iranians will not interfere in any details related to the political process," the memo read, continuing to say that choosing a new prime minister is "an internal affair they will not go deeply into" and it is up to Iraqi leaders to decide who they find appropriate for the position.

The message was not new but a confirmation of an earlier notification delivered by General Esmail Qaani, Qassem Soleimani’s successor as head of Iranian field operations in the Middle East, who visited Iraq at the end of March.

When Qaani arrived in Baghdad late on 30 March, Iraq was locked down, struggling to contain a coronavirus outbreak and seeking a prime minister who could secure the support of enough political parties and lead the country out of half a year’s political limbo.

Despite the lockdown, the Quds Force leader met the next day with the leaders of a number of Shia political blocs, including: Ammar al-Hakim, leader of al-Hikma; Nouri al-Maliki, head of the State of Law, Hadi al-Amiri, chief of the Iranian-backed parliamentary al-Fatah bloc; and Faleh al-Fayyad, the chairman of Popular Mobilisation Authority (PMA) and national security adviser.

Surprisingly to many, Qaani did not meet any leaders of Iraq’s powerful Iran-backed armed factions.

According to a prominent Shia leader who attended these talks, “the meetings were political and did not address any military or security details”.

But the message that Qaani conveyed through the four leaders, the politician told Middle East Eye, is that "the Iranians will not interfere in the details, nor will they impose a specific name for the prime minister. However, they will not support a prime minister who is hostile to Iran or professes hostility to Iran's allies inside Iraq”.

Qaani spent no more time in Baghdad than he needed to, and went the next day to Najaf to meet the influential Shia cleric Muqtada al-Sadr, as has been widely rumoured.

But rather than meet Sadr, he spoke with Sayyed Muhammad Redha al-Sistani, the eldest son of Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani and his office manager, several sources familiar with the visit told MEE.

The reasons Qaani cancelled on Sadr, instead relaying his message through Abu Duaa al-Essawie, one of Sadr’s prominent aides, are unclear. However MEE understands that the cleric was upset by the cancellation.

The meeting with Muhammad Redha lasted for more than two hours. Qaani carried a clear message from Iran's Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei that the grand ayatollah’s "satisfaction is a priority for the Iranians and they are ready to discuss any settlement proposed by him”, the Shia politician said.

Sistani's demands were clear: any political, security or economic agreements between Iran and Iraq must must be exclusively reached through official government channels, as two counterparts.

Any support for any Iraqi force that defies the state must be stopped, Sistani demanded, adding that the Iranian Revolutionary Guards and al-Atalaat intelligence should not be allowed to deal with any political or military force in the country except through government channels.

A close associate of Sistani confirmed Qaani’s meeting with Muhammad Redha, and said that most of the discussion was focused on “the Iranian practices in Iraq that aroused Sayyed Sistani's ire and how to please Najaf [the grand ayatollah] at any cost”.

A first test

The formation of a government and premier to succeed Adel Abdul-Mahdi, who resigned in November amid huge protests, was the first test of Iran’s sincerity.

Particularly so, as an agreement had been hatched in February between the Revolutionary Guard and some Iraqi Shia forces to sabotage any progress towards building a new government and maintaining Abdul-Mahdi’s caretaker administration. Furthering the political limbo, they then thought, would give them time to arrange matters in their favour ahead of any future parliamentary elections.

Things had changed since then, however.

The Shia parties were in disarray after the failure of Mohammed Tawfiq Allawi, Sadr’s candidate for prime minister, to be voted into office.

For eight weeks, they struggled to agree on another candidate, due to “the absence of the high leadership that had united their positions”, a Shia leader close to the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Quds Force told MEE, referring to the power vacuum left by Soleimani.

Instead, Iraqi President Barham Salih assigned Adnan al-Zurfi, the former governor of Najaf and one of al-Nassir bloc’s leaders, to form the government on 17 March, ignoring his constitutional obligation to task the candidate of the largest parliamentary faction.

The nomination of Zurfi, known for his closeness to the Americans and his hostility to the Iranians and their allies, provoked the leaders of al-Fatah and the Iranian-backed armed factions, who quickly declared their rejection of his nomination and questioned its legality.

However, Iran’s refusal to intervene confused its ally al-Fatah, allowing the al-Hakim bloc, former prime minister Haider al-Abadi and Amiri to take advantage and make an agreement with Salih and Sadr to nominate intelligence service chief Mustafa al-Kadhimi, who enjoys good relations with local and international powers, including Iran and the US.

Qaani, who visited Iraq at the height of the struggle between the Iranian-backed groups and their rivals over the next prime minister, did not seek to rally support for any candidate. Instead, he only conveyed the message he came for, three sources familiar with Qaani’s meetings told MEE.

"We learned that a decision had been issued by the supreme leader to end Iranian intervention in the Iraqi file and stop interfering in any details concerning the Iraqi affairs, except strategic issues,” the head of a Shia political bloc, who declined to be named, told MEE.

"None of the Iranian officials discussed any details related to the formation of the new government or the proposed ministers or ministerial quotas, as Soleimani had previously done,” he added.

"The formation of Kadhimi’s government is the first file they have not interfered with that much. We are still waiting to see how they will handle the rest of the files.”

Conflict between allies

The Iranian decision to step back, not have heavy involvement in the next premier’s designation, and turn a blind eye to Kadhimi’s close relationship with the US, has angered Iran-backed armed factions and sparked differences between them.

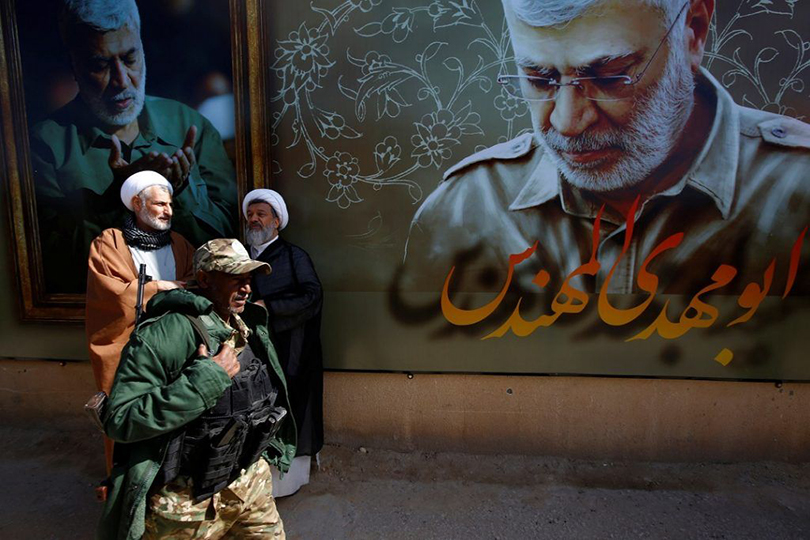

Kataeb Hezbollah, one of the most powerful Iraqi Shia armed factions, was chief among those. The group accuses Kadhimi of involvement in the US’ January assassination of Soleimani and its founder Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis.

Thaar Allah Brigades, al-Khorasani Brigades and al-Nujaba Movement also refused to accept Kadhimi, and held Iran "responsible for the consequences that will result from the new Iranian decision", an al-Nujaba commander told MEE.

Asaib Ahl al-Haq, the second most powerful Shia paramilitary, and Jund al-Imam Brigades, have approved the decision - “but they regret it”, the commander said.

A third faction, including the Badr Organization and Sayyid al-Shuhada Brigades, have meanwhile lined up alongside Kadhimi.

Ahead of the parliamentary vote to put Kadhimi in power, a number of Fatah leaders began mobilising to block him by voting against on the pretext of not obtaining their quota of ministries usually allocated in government formation.

However, an Iranian delegation headed by Hassan Danaie, the former Iranian ambassador to Iraq who is currently in charge of Tehran's approach to Iraqi politics, arrived in Baghdad three days before the voting session.

His delegation met with the leaders of Fatah and al-Hakim, and repeated the same Iranian line, accompanied this time with "non-binding" advice to stop demanding ministries and vote for Kadhimi.

“Most of Fatah's lawmakers voted in favor of Kadhimi without conviction,” the al-Nujaba commander said.

"The Shia have lost the initiative. Kadhimi is Shia, but he will not work for us and this is a dangerous precedent,” he added.

"Kadhimi did not give us any guarantees. The Iranians allowed a vote on him by taking their hands off the whole issue."

New priorities

Iran’s economic situation is dreadful. US sanctions have bludgeoned it, oil prices are at a historic low, and the coronavirus pandemic has shut the Iran-Iraq border and significantly affected the flow of goods and hard currency between the two countries.

Desperate to reduce pressure on the country, reformulating relations with Iraq, the Gulf states and the US is now top of the Islamic Republic’s list of priorities, Shia leaders close to Iran told MEE.

The outsized influence Iran has had in Iraq can be seen in several ways. Tehran has provided moral and financial support to armed factions and corrupt political forces, and encouraged them to challenge Iraqi laws, intimidate Iraqis, use Iraq to launch attacks on US forces and interests, and impose certain paths on the political and security scene.

In recent months, particularly as Soleimani’s killing almost led to open war between Iran and the US on Iraqi soil, many Iraqis have sought to redress that balance, including Sistani.

For Najaf, the seat of Sistani’s religious authority, handing control of the Hashd al-Shaabi paramilitary forces to the Iraqi government, preventing Iranian security services from dealing directly with Iraqi political or military forces, and limiting the dealings between the two countries to official channels would be the cornerstone of repairing relations between the two countries.

Already the Iranian repositioning has had effects on the Hashd al-Shaabi’s leadership.

The armed factions’ heads have reversed their decision to nominate Kataeb Hezbollah leader Abdulaziz al-Muhammadawi, known as Abu Fadak, as Muhandis’ heir as effective chief of the Hashd.

Now Abu Muntazir al-Husseini, a former leader of the Badr Organization, has been nominated to be the paramilitary’s chief of staff.

Under Khamenei’s orders, the Hashd al-Shaabi are meanwhile prohibited from staging any attacks on US bases, and elite fighters have been withdrawn to form a new faction.

This group, Tehran envisages, will be Iranian funded and equipped, and its action will be limited to confronting US forces when needed. Its leaders and fighters are banned from engaging in politics and must sever their ties to the Hashd.

"The new faction has not yet been formed, and will not fight now. It is a deferred pressure card that will be used later by the Iranians to pressure the Americans in negotiations," a prominent Hashd al-Shaabi commander told MEE.

“They [the elite fighters] do not necessarily have to stay inside Iraq after leaving the Hashd. It is likely that some of them will go to Syria, Iran or Lebanon,” he added.

"The problem is that travel is currently suspended due to the coronavirus pandemic, so we do not yet know what the next step is."

Resetting Iran’s relations with the Gulf states and the US may be greater than Iraq’s capabilities. Nevertheless, Iraq can provide much that Iran needs to ease the impact of economic sanctions on it, in coordination with the US.

There are a few "settlements that Iraq can conclude with the Americans”, according to Fadi al-Shimari, head of al-Hikma bloc.

These include ensuring the continued import of electricity and gas from Iran, allowing Iran to export more oil and turning a blind eye to companies that buy it.

Iraq, also, could seek US permission to pay for Iranian imports directly from its assets in the banks in Caucasus countries, which would help fill Iranian coffers.

“The Iranians believe that Kadhimi will be able to play a major role in achieving these settlements,” said Shimari, who is familiar with the government formation talks.

“When the relationship between the Iranians and Americans improves, the relationship between the Iranians and the Gulf countries will improve automatically.”

Comments