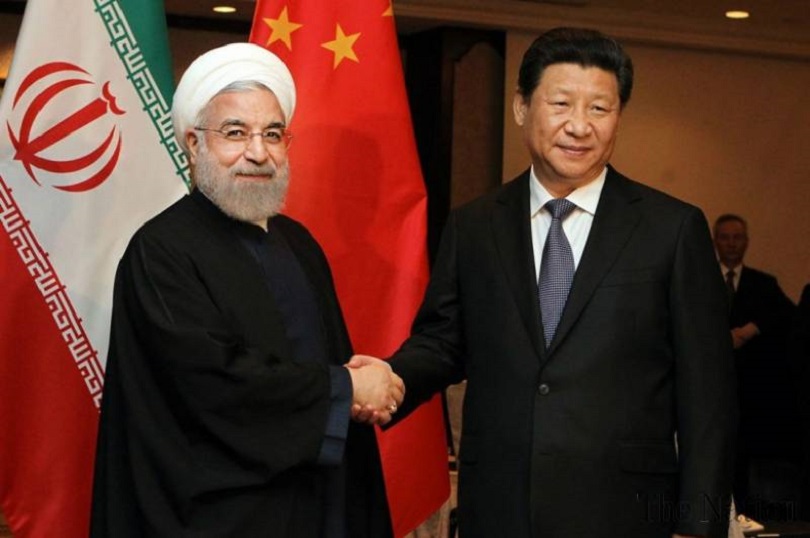

Conventional wisdom has it that China stands to benefit from the US withdrawal from the 2015 international nuclear agreement with Iran, particularly if major European companies feel that the risk of running afoul of US secondary sanctions is too high.

In doing so, China would draw on lessons learnt from its approach to the sanctions regime against Iran prior to the nuclear deal. China supported the sanctions while proving itself adept at circumventing the restrictions.

However, this time round, as China joins Russia and Europe in trying to salvage the deal, things could prove to be different in ways that may give China second thoughts.

The differences run the gamut from an America that has Donald Trump as its president to a Middle East that is much more combative and assertive and sees its multiple struggles as existential, at least in terms of regime survival.

Fault lines in the Middle East have hardened because of Israel, Saudi and United Arab Emirates assertiveness, emboldened by both a US administration that is more partisan in its Middle East policy, yet at the same time less predictable and less reliable.

Add to this Mr. Trump’s narrow and transactional focus that targets containing Iran, if not toppling its regime; countering militancy, and enhancing business opportunities for American companies and the contours of a potentially perfect storm come into view.

That is even truer if one looks beyond the Gulf and the Levant towards the greater Middle East that stretches across Pakistan into Central Asia as well as China’s overall foreign trade.

China’s trade with the United States stood last year at $636 billion, trade with Iran was in that same period at $37.8 billion or less than five percent of the US volume.

The recent case of ZTE, one of China’s largest IT companies, tells part of the story.

Accused of having violated sanctions, the US Department of Commerce banned American firms from selling parts to ZTE, bringing the company to near bankruptcy. Mr. Trump appears to be willing to help salvage ZTE, but the incident significantly raises the stakes, particularly as China and the United States try to avoid a trade war.

That is but one consideration in China’s calculations. Potentially, other major bumps in saving the nuclear agreement lurk around the corner and could prove to be equally, if not more challenging.

Tensions in the Middle East are mounting. The fallout of Mr. Trump’s recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel and seemingly unqualified backing of Israel in its almost certainly stillborn plan for peace with the Palestinian is reverberating.

Discontent across the region simmers just below the surface, magnified by youth and next generations in countries like Syria and Yemen who have little to look forward to.

The bumps fall into three categories: the degree to which China feels that it can continue to rely on the US defence umbrella in the Gulf; pressure on China by Middle Eastern states to shoulder the responsibility that comes with being a great power, if not take sides; and change in a region that is in a process of transition that is volatile, violent and could take decades to play out.

Yet, as China takes stock of the Middle East’s volatility and China’s strategic stake in regional stability, it appears ill-equipped to deal with an environment in which its traditional policy tools either fall short or no longer are applicable.

Increasingly, China will have to become a geopolitical rather than a primarily economic player in competitive cooperation with the United States, the dominant external actor in the region for the foreseeable future.

China has signalled its gradual recognition of these new realities with the publication in January 2016 of an Arab Policy Paper, the country’s first articulation of a policy towards the Middle East and North Africa.

But, rather than spelling out specific policies, the paper reiterated the generalities of China’s core focus in its relations with the Arab world: economics, energy, counter-terrorism, security, technical cooperation and its Belt and Road initiative.

Ultimately however, China will have to develop a strategic vision that outlines foreign and defence policies it needs to put in place to protect its expanding interests; its role and place in the region as a rising superpower, and its relationship and cooperation with the United States in managing, if not resolving conflict.

To be sure, China is taking baby steps in that direction with its greater alignment with international moves to combat Islamic militancy even if its campaign in north-western China risks straining relations with the Islamic world, the creation of a military facility in Djibouti, work on a naval base in Pakistan’s Jiwari peninsula, and cross-border operations in Afghanistan and Tajikistan.

Those may be the easier steps. Dealing with partners like Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates that seek to establish regional hegemony by imposing their will on others at whatever cost may be more difficult. So far, Saudi Arabia and the UAE have not pressured China to choose in their rivalry with Iran.

But it can only be a matter of time before they do, particularly if Chinese investment in Iran and trade were able to offset the impact of US sanctions to the degree that the Islamic republic is not forced to compromise. To evade that situation, China has offered to mediate between Saudi Arabia and Iran, an offer the kingdom was unwilling to take up.

China is not immune to Saudi pressure. To protect their Saudi and UAE interests, Chinese alongside Hong Kong and Japanese banks refused earlier this year to participate in a one-year extension of a $575 million syndicated loan to Doha Bank, Qatar’s fifth-biggest lender.

Similarly, Saudi Arabia in April forced major multi-national financial institutions to choose sides in the Gulf spat with Qatar. In response to Saudi pressure, JP Morgan and HSBC walked away from participating in a $12 billion Qatari bond sale opting for a simultaneous Saudi offering instead.

The stakes for Saudi Arabia in Iran are far greater than those in Qatar. Iran poses an existential threat to the House of Saud for reasons far more intrinsic than the accusations Riyadh lobs at Tehran. The more Iran is able to defeat US sanctions, the more Saudi Arabia is likely to push China and to reduce their support of the nuclear agreement.

That pressure can take multiple forms. With US-backed efforts at regime change in Tehran potentially on the horizon, Saudi Arabia has put building blocks in place over the last two years.

Large sums originating in the kingdom have found their way to militant, virulently anti-Shiite, ultra-conservative Sunni Muslim madrassas or religious seminaries in the Pakistani province of Balochistan that borders on the Iranian province of Sistan and Baluchistan.

A Saudi thinktank allegedly backed by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, has developed plans to stir unrest among the Baloch minority in Iran, partly in a bid to complicate operations at the Indian-backed port of Chabahar, a mere 75 kilometres up the coast from Gwadar, a crown jewel of the China Pakistan Economic Corridor, China’s $50 billion plus Belt and Road stake in Pakistan.

China, moreover, has so far relied on its economic clout as well as Saudi Arabia to remain silent about a crackdown in Xinjiang that targets Islam, putting the kingdom as custodian of Islam’s two most holy cities in an awkward position.

The long and short of all of this is that, in an environment in which the Middle East views conflicts as zero-sum games, China is likely to find it increasingly difficult to remain aloof and straddle both sides of the fence. Salvaging the Iranian nuclear deal could come at a cost China may not want to pay.

Comments